It’s been a year since my most successful experiment. I had given up animal-derived foods to find out what it did for my health. After 30 years of indiscriminate eating, I finally gave the ethical issue surrounding animal food some honest thought, and ended up going vegan completely.

It’s been the best year of my life, and I’m convinced veganism is a large part of that. I won’t gush about the details but I’ll say that I felt altogether better physically and emotionally and I’m never going back to the way I used to live.

However, I don’t want to call myself a vegan any more. I’m giving up my V-card.

I’m still off meat and dairy and eggs, I still won’t buy wool or leather, I still won’t use animals for my entertainment, and I wish others would do the same. But my philosophy on it is quite different than it was a year ago and I don’t want to call myself the V-word. I’ll tell you why.

The first thing you notice when you go vegan is that everyone is mad, and they tell you you’re mad. You voluntarily enter the moral Twilight Zone. You discover a grotesque inconsistency between the beliefs people express and their behavior. You realize that we’re all highly irrational, and that it’s emotion that rules culture, and culture rules the behavior of individuals. No matter how much harm it causes, nothing we do needs to be justified as long as it’s popular enough.

Ask ten people on the street if they think it’s wrong to injure or kill animals for one’s amusement or pleasure, and nine or ten will say yes, of course. Chances are all ten of those people freely consume animal products, simply because they like to and they’re used to doing it.

A new vegan also encounters a bizarre compulsion in many otherwise friendly people to talk as loudly to you as possible about how delicious and juicy steak is. A certain contempt for you emerges seemingly from nowhere, and the most polite person can be overtaken by an urge to reiterate to you that they could never give up meat, because they just “love a good steak!”, presumably the way Michael Vick once loved a good dogfight.

For the recently converted, this inexplicable pseudo-hostility from everyday people can be alarming and it often triggers the kind of inadvertently sarcastic tone you saw in the last few paragraphs [Sorry! -D]. The effect is draining and alienating, and it’s hard not to feel a vague resentment for (or at least disappointment in) the ninety-nine percent of people who have no hesitation about exploiting animals if there is something enjoyable to be found in it.

Tearing down the wall

Sometime last year I was listening to a vegan podcast in which the host announced that after months of examining her philosophies and liefstyle as a vegan activist, she realized she just couldn’t bring herself to dine with non-vegans anymore.

I understood where she was coming from, not that I’d ever do it. Imagine that everyone around you is indulging in something you think is horrible and unnecessary, and you’re supposed to be content to merely abstain from doing it yourself, and enjoy what you can about the surrounding social experience. Imagine realizing you’ll have to do this on a regular basis for the rest of your life. I can understand wanting no part of it.

But it didn’t seem right. Is this where veganism, as a personal commitment, inevitably leads — to a definite social divide between vegans and non-vegans? If so, the only hope for resolution is to nurture the vegan population to grow from the sub-one-per-cent level it is at now, to becoming as normal as being a non-smoker is today.

For most of the last year I felt that divide, not just between me and the omnivores, but the vegetarians too, who abstain from only one kind of animal exploitation. And not just the vegetarians, but the “vegans” who eat fish occasionally, or the ones who eat vegan but wear wool peacoats.

I even felt it between me and other vegans. I was an abolitionist, which basically means zero tolerance for any avoidable use of animals. But on the other side of the fence there were also welfarist vegans, who spent their time campaigning to improve conditions for food animals, encouraging vegetarianism or Meatless Mondays or other “partway” measures that make abolitionists cringe.

This alienation is real and I doubt there’s a single vegan (or vegetarian) reading this who doesn’t experience it. Right from the start it was always the hardest part of being vegan. It wasn’t the food cravings, it wasn’t the reduced clothing selection, it was the social weirdness that emerges when people learn you’re “one of those.”

In social situations — barbecues, parties and dinners out — people are generally polite and accepting, but they still can’t help but treat me as a special case with my special-case food. They probably can’t quite see me as a full participant. They make it clear that they have absolutely no desire to become a special case themselves, who isn’t “allowed” to do what normal people do. They are usually trying to be kind, but it still creates weirdness on both sides of the wall.

Now it’s clear to me that it’s the label that’s the problem. Not the labeling of food, or shoes, but of people. I think it creates animosity on both sides, it defines the wall itself, and that prevents that wall from moving much. It seems that generally, vegans love their label, and love to deny it to non-vegans. If you were to tell a group of vegans that you’re a vegan who enjoys a tiny cube of cheese once every leap year they’ll say, “Oh so you’re not vegan then.” And technically they’re right.

I think how we broach the issue with members of the omnivorous majority is extremely delicate, and most of the time it’s done badly. The word vegan has extremist connotations to most, and no matter how much the vegans think that’s undeserved, it is ultimately the omnivores who decide how quickly veganism is going to grow.

The end of us and them

So I tossed the label. I haven’t changed much about how I live, but I won’t call myself a vegan any more. It’s a handy label for classifying recipes, cookbooks, how certain products were made, but I won’t wear the badge any longer. Technically I don’t reach the bar anyway (as 99.5% of people don’t) because I ate two slices of pizza when I went to New York last month.

There are two main differences in how my new philosophy affects my behavior. They’ve made life so much easier on me, and have made me a better ambassador for the cause of moving away from using animal products.

1) I am careful not to harbor or express disgust for non-vegan food. When you learn about where meat, dairy and eggs come from, it’s hard not to feel disgust, even if you don’t change how you live in response. Most vegans feel some of this disgust whenever they look at those foods. Many won’t even acknowledge that it’s food.

I now see this disgust as a hindrance to the spread of animal-free living. The net effect of that disgust, more than anything, is that omnivores feel judged or dismissed by vegans, and begin to resent them. Staunch vegans might say “Who cares if they’re offended man, I’m doing what’s right.” — forgetting that souring people to veganism who might otherwise have become vegans is effectively erasing all the good they have ever done, and more.

A fellow blogger who calls himself Speciesist Vegan wrote a great piece here on why it’s so important for vegans to get over their disgust for non-vegan food, if they want veganism to grow.

2) I make the occasional exception when it comes to food and I don’t hide it from the omnivores in my life. There are three reasons I do this now. First, it demonstrates to them that I don’t think they’re disgusting or immoral, and that my philosophy on life is not categorically different than theirs. Second, by deliberately indulging in the odd act of exploitation, it eliminates the feeling of being permanently “outside” the world of normal people, by being someone who will die without ever eating ice cream again. And third, it shows them that how I live isn’t difficult, isn’t all or nothing, and is something they might actually do themselves.

I fully understand there are people who want absolutely nothing to do with having an animal food in their mouth again, and see no need to alleviate the social alienation by eating the odd non-vegan item, but I’m no longer one of them and I believe what I do does far more good than harm.

I also don’t go to great lengths to ensure a meal is vegan before I order it in a restaurant anymore. I will eat the free bread, with no investigation. Much more effective, I think, than nitpicking my way around every sprinkle of parmesan and every stick of egg-white-brushed complimentary bread, is to demonstrate that you can be a normal participant in everyday social activities while still avoiding animal products almost all the time.

A new vegan should realize relatively quickly that the vast majority of people alive today have zero interest in veganism and will never do it no matter what you say to them. The single notion of “no more ice cream, ever” is, I’m sure, an utter dealbreaker for the majority of people. Only a small proportion could potentially become strict vegans, and I think our energy is better invested in trying to get the larger proportion to experiment part-time with vegan options, rather than trying to get people to completely defect to the as-yet-tiny “other team.”

Looking at the endless internet banter whenever the issue comes up, what most vegans seem to forget is that for somebody to go vegan, it means an omnivore has to see veganism as something more appealing than what they already do. Yet they insist on driving home how uncompromising and all-or-nothing it must be. If you don’t believe me, go post “I avoid all animal products but honey and silk” on a vegan message board and look at the responses.

I indulged in this smug partisanship too. There is an abolitionist blog I once really enjoyed, even though it consisted almost entirely of ripping into celebrity vegans who go back to eating eggs occasionally.

I believe that in the current social climate there are probably twenty times more people out there who would potentially go 90% of the way to veganism, given the health, environmental and ethical incentives, than there are people who would ever arrive at a day when they declare they’ve had their last ever Ben & Jerry’s. There’s way more ground to be made — which represents many more animals to be spared — influencing the former group than the latter.

Between my abolitionist days and today, the difference in the volume of animal products I consume is pretty small. A few more of my dollars do go to paying people for exploting animals. These changes may represent the difference between say, 99.8% of my total buying power, and 99%. (Despite what some vegans may tell you, it is unlikely anybody is able to live 100% vegan, but you can get really close.)

But if my more relaxed, undogmatic lifestyle convinces even one person that they could live without animal products, even 50% of the time, I’ve already prevented more many times more harm than I’ve caused.

What I want is for the world to move away from using animals for their pleasure or convenience. I no longer believe that growing a small but intense group of zero-tolerance advocates is going to do that. It is easier and mathematically more effective to convince several times the people to go even just halfway.

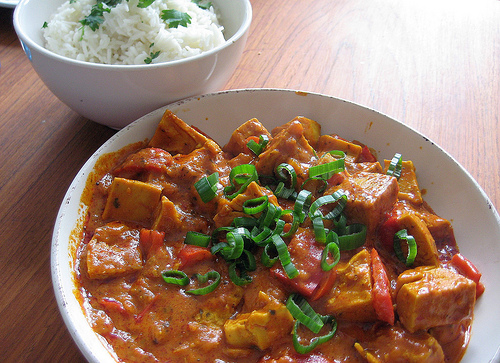

But more importantly, it invites a culture where a large proportion of people have taken some action to reduce animal use, and have been exposed to the reasons why it might be a good idea. Right now, most people don’t honestly believe it’s possible to even have a delicious vegetarian meal that doesn’t seem like a compromise. I think encouraging them to cook their first enjoyable animal-free meal is more effective than posting abused pigs on their Facebook wall.

The biggest change I want to influence people to make is to find a personal philosophy that resonates with them most, rather than interviewing the various camps and joining one. [This perspective is often cited in positive reviews of Jonathan Safran Foer’s Eating Animals — an anti-eating-animals book that’s ripped on as often by strict vegans as it is by anti-vegan omnivores. The reviews, generally, are glowing. Foer is not vegan.]

I think we’re better off easing the general population into no-pressure experimentation with animal-free food and clothing than we are insisting you’re either carrying the V-card, or you’re part of the problem.

Vegans, non-vegans, in-betweeners, what do you think?

###

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

Comments on this entry are closed.