I was 31 when I figured out breakfast, and after that life’s overall difficulty level declined a bit.

Every month I buy a bag of bulk steel-cut oats, a bag of trail mix and a six-pound bag of Royal Gala apples. Every morning I make a heaping half-cup of the oats and cut an apple into slices. About six months ago I added a cup of Ceylon tea to that.

That’s breakfast every day now. I used to keep my options open, figuring that going with what I “feel like” in the moment is going to naturally lead to a more appropriate, fulfilling breakfast experience.

After years of being confronted with a decision shortly after waking, I decided to be done with deciding what was for breakfast. My usual is now the only thing on the menu, and since I stopped deciding what’s for breakfast, mornings have had a significantly different feel. They are clearer and more spacious.

I thought my newfound clarity was a byproduct of having more whole grains in my diet, or the self-satisfaction of finding a breakfast that costs 11 cents. I now believe it has nothing to do with oatmeal at all, but rather with the fact that I have much more than 11 cents to spend on breakfast, and in today’s global food system that gives me way too many options.

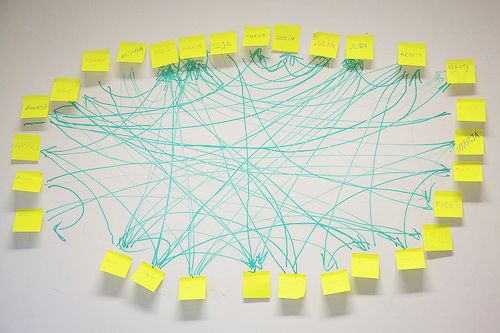

As affluent Westerners we’re fortunate to have so many choices, but according to psychologist Barry Schwartz, having too many possibilities — which we do in almost every area: breakfast, clothing, careers, lifestyles and creative pursuits to name some major ones — makes it consistently harder to be happy with the options we choose. In his TED talk he identifies the ways too many choices erode personal welfare instead of serving it.

When we’re faced with a number of options, we’re always going to assume that one of them is better than all the rest. This means the more options there are, the more likely we are to choose one that isn’t the best one. We also presume it would take more homework to choose the right one. In other words, as options increase every decision becomes bigger, and so the more likely we are to delay our decisionmaking.

Facing any decision is to some degree stressful, whether it’s picking a menu item, or picking an investment vehicle for your retirement. Delaying decisions because you don’t want to make the wrong decision only compounds this stress. This trepidation is a fear of future regret, and the resulting paralysis can lead to procrastination, which in turn leads to self-esteem issues, which only compounds indecisiveness further.

Even once you make a decision, the more options you turned down the more likely you have lingering doubts that you missed the boat — or at least, some boat. Even if you make the best choice, you never really know that, and you’re likely to wonder what you’re missing.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

After countless attempts to establish new ("good") habits and relinquish old ("bad") habits, this got me thinking: What if the habit I really need to establish is a practice of self-discipline? I have begun asking myself regularly, "What would a person with self-discipline do here?" Most times, the answer is...