On Twitter the other day someone asked why he should continue to experiment with mindfulness meditation — specifically, what does it do for you when you’re not meditating?

Others and I gave the usual replies: you don’t get stuck in rumination as easily, you better appreciate the ordinary sensations that make up life, and it helps you suffer less over your pains and get less addicted to your pleasures. It seems to shift your natural inclination towards healthy behaviors, and away from unhealthy/self-defeating behaviors.

However, saying all that doesn’t clarify why mindfulness meditation might do those things. Does closely observing the flow of your experience just make you a better person somehow?

I would say… yes, probably. A wiser person, at least. Meditation makes you wise, and wisdom makes better ways of living feel more natural, and worse ways feel less natural.

But how? Reflecting later on how my response didn’t answer the poster’s real question, I thought of an analogy that might do a better job.

If you were to sit on the edge of a ski slope and watch people ski by, you’d notice a big difference in how the more experienced skiers handle the slope’s bumps and rises.

New skiers, if they see the bump coming, will brace themselves for the sudden change in trajectory by stiffening their legs. They’ll probably go, “Oooohwoooooooah noooo!”, lose contact with the ground, and maybe crash. If they don’t see the bump coming, trouble is even more likely.

Experienced skiers will simply let their lower body rise and fall with the bump, taking in the knees as needed and reducing the jarring change in trajectory. Their upper body might not even deviate from its downhill path.

Not only does this maneuver prevent one from wobbling and crashing whenever there’s a bump, but adjusting in real time like that feels really good. Your body feels connected to the terrain, rather than opposed to it. This non-contentious relationship between skier and terrain not only feels better, but it affords better control and speed, as well as being safer and looking pretty awesome.

Even when the experienced skier doesn’t see a given bump coming, they know to remain supple and responsive enough to adjust in real time should one appear. There are only so many things a ski slope is going to do, so after a certain amount of attentive skiing, true surprises are rare. It’s as if the body becomes wise to the way ski slopes are, or tend to be, and as a result just knows how it should be at each moment.

Even if you’re not into skiing, you undoubtedly already possess this sort of wisdom in some form. New drivers nervously run through a mental checklist while backing out, parking, or switching lanes, while an experienced driver will just do it all by feel. The hands and feet just know the right moves, the right pressure to apply to the pedals, shifter, and steering wheel. The better you are at it, the less conscious control you need to exert, and the better it feels.

A certain amount of familiarity with the “terrain” of a given task will always result in this sort of bodily wisdom. If you’re very experienced with typing, your fingers just find the right keys. They know when to slow down to accommodate a tricky sequence. The ring finger knows to tap Backspace after an error, and the thumbs know the spacebar like Yo-Yo Ma knows a cello. To experienced typing fingers, the terrain is familiar even in its irregularities, so the whole operation flows smoothly with minimal frustration and maximum wpm.

What if you could generalize this incredible wisdom-generating process? What if there was a way you could train your whole mind-body system to gracefully handle the bumpy terrain of everyday life, regardless of what form it took: disappointment, elation, uncertainty, temptation, overexcitement, shame, expectation, tension, and everything in between?

Imagine this training allowed you to cruise smoothly over all these familiar contours in a way that felt good, at least more of the time.

Mindfulness meditation is essentially that. You set aside time to practice observing your experience, keeping a certain mental suppleness and receptivity towards whatever comes along. During this time, you deliberately allow experiences that normally make you stiffen, grasp, or react — such as uncomfortable bodily feelings, recurring thoughts, cravings to fidget or scratch, pangs of boredom or hunger, impulses to relive remembered conversations, and a thousand other impingements on your designated quiet time. You do your best to stay neutral and accepting, appreciating the harsher contours just as you do the smooth and easy ones.

And it’s all bumps, when you look closely. Our untrained mammalian instinct is to sort moments into good and bad, wanted and unwanted, triggering countless unchecked aversions and cravings that spike our cortisol, exhaust us, and drive self-destructive behavior.

The more you practice, the more you see that it’s not the bumps that are the problem, but our stiff, instinctive reaction to them. The bumps will always be there. They are life itself.

And because the bumps are life itself, the skill and wisdom generated by mindfulness practice is relevant at all times. No matter how many bumps there are, or what they look like, it’s the same response that will allow you to navigate them smoothly: a certain learned suppleness and receptivity in the mind, which you develop by practicing it directly.

In other words, mindfulness is a way of getting very familiar with what it feels like to be a human being, on the most granular level possible: the moment-to-moment unfolding of sensation. Every speck of our experience is made of sensation: all pains, pleasures, thoughts and feelings, including your body’s and mind’s reactions to other sensations. To practice is to make the most thorough possible study of not just the slope’s terrain, but of the skier’s relationship to it in each instant (and how you are actually both the skier and the terrain when it comes down to it, but that’s another post).

Of course, if you want to get good — which is to say, wise — at some specific human endeavor, like skiing, driving, public speaking, or typing, there’s no replacement for getting familiar with that particular type of experience. If you want to get good at being human in general, I don’t know a better way than to sit and observe momentary experience as it unfolds, with as much receptivity as you can muster. And if you’re doing that, you are meditating.

UPDATE (April 2024):

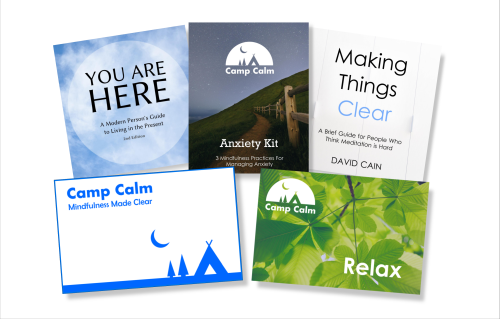

It’s a good time to try out meditation right now, if it interests you. We’re having a one-time sale for Raptitude’s 15th anniversary. I’m offering all of my mindfulness resources, in a single bundle, for a huge discount.

That includes five things:

- Camp Calm: 30 Days of Mindfulness (course) Develop a simple, consistent meditation practice over a 30-day period.

- Camp Calm Relax: Mindfulness for Relaxation (course) Learn a meditation technique designed to promote physical and mental relaxation.

- You Are Here: A Modern Person’s Guide to Living in the Present (ebook) Explore ideas and techniques for practicing mindfulness in daily life.

- Making Things Clear: A Brief Guide for People Who Think Meditation is Hard (ebook) Learn to avoid the common ways people make meditation harder than it needs to be.

- Camp Calm Anxiety Kit (ebooklet) Three mindfulness techniques for managing anxiety.

All of these resources work as standalones. You can read the books and do the courses in any order, at any time.

Full price for the collection is over $200. As of right now you can get it all for $79 USD*. This is less than the price of Camp Calm by itself.

You’ll have lifetime access to all the material. Also, those buying the bundle will be invited to participate in future group sessions of Camp Calm, for free. There will be a group session later this year, but by then the course will be full price.

This sale will only be on for ten days, starting now, and then that’s it. After that I’m gone on a meditation retreat of my own, totally offline, so there can be no latecomers!

There are lots of ways to learn mindfulness skills – this is by no means your only chance to do that. But if you like my approach to things, this might be a good way in for you, and today might be as good a day as any to start.

***

***

Photos by Maarten Duineveld, Jared Rice, Austrian National Library, Cytonn Photography, DimiTalen, David Heslop, and Sebastian Staines

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

So good, David. One of your very best. Deep, clear, simple, practical wisdom. Not easy to do, of course, but simple to understand as you stated it.

Thanks Ron. I might write a post about how easy meditation is or isn’t, because I think it depends a lot on perspective. I know I made it much harder than it was because of how I approached it.

For now I’ll say that it’s really hard when you emphasize the goal of staying “focused” on the meditation object, and quite a bit easier when you emphasize the goal of exploring/getting-to-know the meditation object.

Just want I needed to read. Thank you for sharing your wisdom David.

Thank you!! This is so wonderfully written. Explains so well, why meditation can help…

great

“The more you practice, the more you see that it’s not the bumps that are the problem, but our stiff, instinctive reaction to them. The bumps will always be there. They are life itself.”

Brilliant way of explaining how meditation enables a more fulfilling life.

Agreed, brilliant. I’m going to keep returning to these words. As a daily meditator of three years, I think this is a beautiful description.

This is great stuff. The analogy of the skier and terrain is amazing, something to not only clarify the motivation and foundational reason for acquiring the meditation skills, but also provides a great mnemonic for those moments when I realize I’m tensing up out on “the slope.” Thank you!

Right. We’re always on the slope, and there’s always bumps. There’s no way not to be on the slope, or for the slope not to have bumps, so it’s all a matter of mastering that quality of suppleness/receptivity.

Ah, the human experience! Seemingly so simple at times, and other times so complex. My ‘mind wandering’ about mindfulness is: about the person(s) who figured this out (Buddha et al). Through meditation and mindfulness, did they see the process of daily living, with its twists and turns, and use mindfulness as a way to overcome the built-in challenges? Or, did they somehow see that living mindfully is the indicator of humans next step in evolution? A way ‘around’ Nature or a way to fully participate?

We certainly have different applications for mindfulness than the Buddha would have had. As far as I know for him it was a tool to cut right to the fundamental characteristics of existence. I think most Westerners have to start with a more materialist/practical idea of what it can do.

This might be the single best explanation I’ve read about how and why meditation works. And David, I would not be a meditator without you. I’ve taken your Camp Calm course twice. In March, I celebrated my 70th birthday by going to a yoga and meditation retreat in Rishikesh, India. Thank you!

Oh nice! Glad I could help you find the path/slope :)

Currently I happen to be reading Head Off Stress, by Douglas Harding, whom I first heard about reading your blog. Doing his practical experiments isn’t much different meditation (maybe it’s the same!).

You could call Harding’s practices a form of self-inquiry meditation. They are taking a different path from the mindfulness-first approach, but to the same place in the end. In mindfulness you’re developing attentional skills that can later be turned on the nature of existence (what is the self, who is suffering, etc.) In self-inquiry you’re shooting straight for insight into the nature of self.

I’ve been through some pretty significant bumps shredding the slopes of life…. I started meditating around twenty years ago. Dove quite a bit deeper when I started reading your blog around 2009. I’ve been practicing daily for several years now….

Back to the bumps…. I’m sure I would have made through them without meditation. It’s like fly an airplane.

Nobody gets stuck up there. But I shudder to think of the possible outcomes I might have experienced had I not had my head properly screwed on thanks , in no small part,

to my practice. Your blog was enormously helpful as well David.

Very fine of you to encourage people to come to meditation….. “It’s the crux of the biscuit”

This was a pleasure to read.

I will add: what I have found extremely helpful as well, and somewhat different to meditation, is simply “downtime”. That is: You don’t even try to observe or focus on something. You just sit down, stand your ground, and do absolutely nothing, for any amount of time (e.g. 5-60min). This can be quite hard in the beginning. But it allows your mind to go through all sorts of unprocessed thought& inputs and reorganise itself. Actually, while doing this, I realised, that most of the time when I come back from something exhausted and turn on the TV, what my mind actually demands is not other input, but simply downtime. In terms of work, it also has the benefit that it replenishes your clarity, rather than depriving you of it. Thus, if you don’t feel like doing something what you objectively should do (let say, studying), downtime is always a safe alternative. If you actually need rest, you can take it, and it will feel much easier to proceed with your plan afterwards. If you do not need rest, the lack of sensory distractions will make your task feel far more enticing after a just a few minutes.

I do this more and more. My teacher Shinzen has a way of formalizing the sort of practice you mention into a simple (but not easy) technique called Do Nothing.

It only has two instructions really:

1. Let whatever is happening to happen

2. When you notice an intention to direct your attention to something in particular, drop the intention

So you’re really just letting your attention land on whatever it naturally lands on, and jump from thing to thing, and you simply allow it to do that. Really incredible what happens when you cease making the mind do stuff like that.

I’m currently listening to “The Master and his Emissary”, about the right and left hemispheres of the brain. In this short video Iain describes how conscious attention is different in each hemisphere, and how meditation can help balance the hemispheres.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vkmYzbwrufg

An excellent post. Though I do not mediate, per se, two thoughts came to mind. The first speaks directly to your point. Many years ago I was a professional driving instructor. The instruction I gave more than any other was to relax. If your arms aren’t relaxed (and by default your mind and body) you can not drive or perform other complex physical activities well. This, to me is that flow state that is most effective. My second thought revolves around my artistic and written endeavors. When I paint, create digital art and oftentimes writing, it’s as close to meditation as anything I’ve heard described. I’m totally focused, in the moment and unaware of what’s around me our how I feel physically or mentally.

Comments on this entry are closed.