I have a radical proposal. An experiment that might just change your life. If you want to try it, I’ll do it with you.

It goes like this:

Live most of your days according to your normal habits, doing your job and your everyday stuff the same as always. Then one day a week, let’s say Tuesday, you live by a specific dictum:

From the minute you wake up, do without hesitation the thing that most needs to be done in each moment, regardless of how appealing it is. Bring your full attention to each such act, as though it’s your sole purpose on earth. Let go of every other concern.

In other words, on Tuesdays, and only Tuesdays, you devote yourself to doing the wisest and most helpful thing you can think of in each moment, all day long. You don’t try to strike any sort of “balance” between doing what you want to do and doing what you know is best. You choose the latter every time.

If the moment calls for taking a big gross garbage bag to the dumpster, you calmly pick it up and go. If it calls for broaching an unpleasant topic with your boss, you broach the unpleasant topic with your boss. If it calls for starting your term paper today even though you could rationalize waiting till Saturday, you sit down and start. If it’s time to slip your phone back into your pocket rather than scrolling another page of Reddit, you do it.

Doing this stuff feels however it feels, and you don’t worry about anything else. All day long, you simply defer to your honest interpretation of the right thing to do, which is whatever seems to promise the best overall consequences for you, your future self, and the people around you. And you see what happens.

(You can still enjoy any incidental fun, ease, and comfort that comes your way in the process.)

Note that this is not the same as trying to be maximally productive. The moment might not always call for toil or difficulty. When you’re tired and know you should rest, you rest. If it’s movie night with the family, watch the movie with the family. Again, do what you honestly think is the right — and by that I mean the most right — thing to do. Burning yourself out by working till midnight probably doesn’t serve you and others best, so it isn’t the right thing to do.

You will make mistakes, of course. The temptation to compromise, to delay doing what the moment calls for, will keep returning, and sometimes will draw you off course. That’s okay. You will fall short to some degree or another. What matters is whether you’re really trying to do this.

Whatever happens, you don’t cease your effort until you fall asleep that night. Then, for six long days you can go back to your usual compromise between doing the utmost good and doing what you feel like. If you still want to.

That’s the proposal.

What do you think would happen if you did this experiment? Would life get better or worse? Would Tuesday come to feel like a scourge on your week, a Sisyphean death march you wouldn’t wish on anyone, or the day you feel most truly alive and happy with yourself?

Two Ways to be Good (Enough)

I did something like this during my Stoic experiment last year, and have done it many days since, and in my experience those days are hard but immeasurably better than normal days. You feel engaged and unconflicted. You don’t ruminate or worry, because you know you’re making the best day you can. Life feels meaningful and satisfying, and you go to bed with no remorse, which to me felt miraculous. As Marcus Aurelius promised in his version of this dictum, “. . . a man has but to observe these few counsels, and the Gods will ask nothing more.”

Again, it’s not about executing a perfect day. It’s about devoting yourself to the best possible use of your life that day, and seeing what happens.

As I get older, this mode of being — living each day like it’s Do-the-Right-Thing-at-Every-Moment Tuesday — seems increasingly to be the only way of living that makes sense. Dividing your effort between doing the right thing sometimes, and doing the not-quite-right (but easier or more pleasurable) thing other times, seems to betray a somewhat confused life strategy. Essentially you’re playing a game of “One for me, one for my best self and the good of the world. One for me . . .“

It raises an interesting question: who is “me” if it conflicts with your best self and the good of the world? And why are we giving it half the proceeds of our lives?

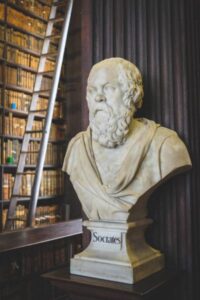

The ancients were on to it, as usual

If you look at what ancient humans say about how to live, it’s always some version of this full-time devotion to good. The Stoic tradition, the Buddhist tradition, and the Biblical tradition all propose an everyday version of Do-the-Right-Thing-At-Every-Moment Day.

They don’t say, “Have a good time, but do enough difficult stuff to be able to consider yourself a good person,” as modernity seems to prescribe, but rather, “Train yourself in each moment to always do the morally best thing, with love and without hesitation. Make this your purpose in life and sacrifice everything else for it.”

The promised reward seems to be that life gets a hundred times better when you live like this, and not just for you. Everyone around you benefits from your actions and example. You aren’t just creating the best possible life for yourself, but the best possible world.

Your actions have a powerful compounding effect, after all. They affect your own future in dramatic ways, as well as the futures of all the people you interact with, and who they interact with, and so on. Every little act, right down to the attitude you’re carrying when you step onto the bus, is a moral choice with ever-rippling consequences. It matters whether you indulge in complaining to your wife about the bad driver you encountered, or whether you look down on your co-worker for her decidedly self-important Instagram posts — and not just a little. Even slight goods and harms can compound easily, in our subsequent actions, attitudes, and relationships, echoing far beyond our own lives and even our own lifetimes. No wonder the ancients got so serious about this.

The Highest Stakes of All

With the stakes of our moment-to-moment conduct being so high, these old traditions tend to frame this elective aspiration as the most serious of moral issues. The first, last, and only moral issue, in fact. We’re faced, they say, with an eternally recurring choice between the freedom of virtue and the shackles of vice. Nirvana and Samsara. Heaven and Hell. The stakes of this battle are incalculable — thus is the human condition and you fail to recognize it at your peril!

Okay — so that sort of dire language might create a little too much pressure for our modern, pleasure-addled minds. (Perhaps it was less of a stretch for beleaguered Iron Age peasants.) That’s why I propose starting with one day a week at first, as an experiment, just to see what this ancient idea has to offer. If that seems like too much, then try a shorter period — say between 9am and noon that day. Begin where it seems manageable, and if it feels like there’s something to it, scale it up.

Either way, I suspect that we put ourselves under greater pressures by not taking up some form of the great ancient moral challenge. Having committed to doing your best, moment-by-moment, is difficult in terms of the day’s effort level, yes, but it also creates constant rewards and an exhilarating sense of relief. For once you’re not trying to get away with anything, and you know it. You’re not doing anything to undermine your own values. You become impervious to most kinds of remorse and worry, because you’re making life turn out the best it can. You’ve unshouldered a load of rocks you didn’t know you were carrying.

When you experience some hint of this sort of clarity, it really does seem like this approach to life, or something like it, is the best idea humans ever had.

Join the experiment

I’m interested to hear what you think of this. Does it sound horrible? Revelatory? Both?

I claim no mastery of this approach to daily life, but I can say it doesn’t stay as exhausting as it seems at first. When you know you’re going to do the right thing at each juncture, you only have to worry about the pain of effort, which is nothing compared to the pain of remorse or self-loathing or meaninglessness. There’s no difficult tradeoff to agonize over — one way is clearly better. You finally get to live as that fortunate Future Self who’s constantly reaping the fruits of your many benevolent past selves.

So I’m serious about this experiment. I’ll be doing it on each Tuesday of November, and will write about it on the experiment page. Join me, and share your experience in the comments.

If you’re intrigued but hesitating, ask yourself why not do it, if there’s so much to gain and so little to lose? It doesn’t conflict with anything important, like your job or family obligations. The opposite in fact.

Personally, the only serious reservation I’m left with is that it’s hard. It’s better, sure, but it’s hard, and when a hard thing is optional I tend to turn it down, because life always seems too hard already. But maybe that’s why.

***

Photos by Vladimir Fedotov, Ekaterina Shakharova, Bryan Woolbright, Aleksandar Cvetanovic, and Pietro Rampazzo

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I’m in, I’m intrigued. I do a lot of the wrong thing, or perhaps I do a small amount of the wrong thing but it takes up a lot of my time in regret and planning not to, so it feels like more than it is. I’m very willing to experiment with this. I like the thought of having only one criterion to make decisions with – “what’s my gut feeling is the right thing to do?” – rather than all the weighing up and pondering I might otherwise do. I’ll try not to get hung up on a head-level assessment of what “the right thing” is and try and trust my gut. Even that will be very good practice – like so many of us, I don’t listen to my gut enough.

Great. It’s definitely still okay use both your rational mind and your intuition to assess what the right thing probably is in a given situation. Those are both tools available to us. However, I think we usually know what we should do, it’s just that sometimes we’re tempted to do the expedient thing, the “good enough for now” thing instead of the right thing — the thing we would do if this were our last chance to do anything. But that introduces competing motives — Good versus convenience, comfort, etc, which not only create worse results but make the process of living and doing much more fraught and complex, because we’re trying to balance multiple motives, rather than living only one the best we can.

Wow. Just the framing of the question made me balk, which consequently led me to realize just how many of my day-to-day decisions are made in spite of what I know is good for me.

What you said about the “one for me, one for my best self and the good of the world” might have been the most profound bit for me. Living like this as most of us do ends up a zero-sum game for both your better self and your selfish self, in which you’re not *really* developing good habits, building skills, or getting stuff done as well as you could…. but you’re also not *really* enjoying being indulgent either due to the guilt and anxiety from knowing you could be making a better choice.

« Wow. Just the framing of the question made me balk, which consequently led me to realize just how many of my day-to-day decisions are made in spite of what I know is good for me «

This was pretty much exactly my reaction too.

It’s a scary prospect but it is only for one day a week so I guess I will try it.

The first Tuesday in question will be interesting as I am on vacation.

That’s the crux of it I think. We’re trying to serve two sets of motives. I’ll explore this idea in a future post, but I think those competing motives (Highest good vs what we want) are really a competition between our older, animalistic drives (seek pleasure and avoid pain) and our newer human capacities for living in ways that reduce suffering for ourselves and everyone else. They sometimes align, and sometimes conflict, and the idea is to renounce the older one as completely as possible to align yourself with the newer one.

This! This was the wow moment for me.

Even this exercise slips right into the list of things I should do and I can feel myself trying to decide between doing the right thing (this exercise) or not doing it and feeling the satisfaction of expressing my free will to not do it. What a racket.

I’m going to do it. And I’m going to keep in my head this line , “who is ‘me’ if it conflicts with our best self and good of the world?”

I’m in. It doesn’t seem that scary to me. Hmm. Maybe I’m looking at it all wrong.

I say if you’re on vacation, maybe indulgence is the Right thing to be doing!

Taking care of yourself is the right thing to do. I don’t think that it is always at odds of the best thing for others or the world. If we feel good then we are able to care for others even better.

On to Tuesday!

Definitely, but remember that there are many interpretations of “take care of yourself.” I think whether you do the right thing is a matter of your level of wisdom and your level of honesty about what that means to you. To indulge with abandon because “hey it’s a vacation” isn’t really dedicating yourself to the doing the thing that needs to be done.

In other words, you really have to think about why you’re taking the vacation. If it’s to rejuvenate yourself from a stressful year, then eating and drinking all day is probably not going be the best path to that end. But maybe nature walks, swims, and massages are. It’s all a matter of continually reflecting on what the highest good would be in that situation.

It points out to me the difference between should and good. I should work on my taxes, but is it to my highest good to take a healthy walk instead. Do you see my quandary?

Do I complete the tasks that cause me stress everyday and remove that stress ir release the stress built up with a massage?

The only quandary is determining what you think the highest good is. Sometimes it’s to just get the thing done. It’s healthier, better, right sometimes. Other times it’s to take a break. “Should” is a red herring here. If the highest good truly is to ignore your taxes and take a walk, then that’s what you should do.

Love it man… Kinda sorta reminds me of a new mindset/book I’m reading too – “Radical Honesty” by Brad Blanton. At least in the “figuring out who I am” department :) Your way also probably helps more people than being completely honest all the time, lol… I bet you’d enjoy reading it though.

Hi J. Radical honesty is essential to this process for sure, because you need to be honest about what the right thing really is. We are very good at rationalizing and deceiving ourselves in order to do less hard stuff.

This is, hands down, one of the best (if not THE best) challenges you have ever proposed. Makes me think of Hhand’s ‘be the change you want to see’ in the world’ – words to that effect. Anyway – you sold me. I’m doing it.

Glad to hear it. Let us know how it goes for you. I’m curious to see if we all run into the same challenges.

I’m interested, but also a little apprehensive. I’m not sure what I’ll do in situations where the choice isn’t obvious. When it comes to work, I have to juggle producing content for my copywriting clients (short deadlines) and working on my fiction books (longer deadlines but so much work to be done). If I listened to what I want, I would write books all day long, but I’m not at that stage of my author career. At the same time, I would end up thoroughly miserable if all I did was write marketing copy. It’s hard. :-/

The choice isn’t always obvious, but in that case the right thing is to make your most honest guess. If you were someone who was going to do her best to do the right thing right now, what would she probably do. If you can’t think of anything better, then that’s it.

And really, we almost always know what probably makes the most sense.

For me that would be an instant choice paralysis. In fact, I’m battling with it on most days, some more, some less. Just WHAT exactly IS the “best” thing to do at any given moment? Should I do my daily job? I’m paid to, after all. Then again, my hours are flexible – I can do something else now and my job later. Should I work on my side project? Should I go and fix the bathtub seals that I’ve been putting off forever? Sort through and dump the junk in the storage room? Or maybe I should focus more on people? My kids have school holidays, maybe I should go and spend the day with one or both of them, doing whatever it is that they like? Or maybe I should focus on my wife and try to make her day the Perfect One? Then again, this is all very local. Perhaps I need to think wider! I could go outside and clean up trash from my neighbourhood. Or join some sort of volunteer organization doing whatever volunteer stuff (so then which one)? Maybe I should donate my money to some charity (which one?) Maybe I should quit my job, abandon everyone and everything, and move away to… do something completely different that I haven’t even thought of yet. Etc, etc, etc. There are SO MANY choices and NO criteria whatsoever that I can think of which would answer the question – “From all of these countless choices, which singular solitary one is The Absolutely Totally Best And Most Useful And Right?”

That sounds like a very high bar! How about “what feels like the right thing to do for the next hour?” Best, Useful and Right could all be different things – how about experimenting with choosing one of those for a day?

“What feels like the right thing to do for the next hour?” – very dangerous, I’ve gotten burned many times with this approach. Your feelings tend to gravitate to the things that you like, not the things that are really needed. It’s very easy to start justifying laziness as “well earned rest” and ignoring other people’s concerns because “I feel like doing this is the best thing”. I’d rather put my feelings aside for such important decisions and try approaching this question somehow logically, rationally.

I’m a writer and a mom of two small kids, and I feel you on the absolute paralysis that comes in when you finally have some time to do SOMETHING other than cater to the needs of tiny tyrants and a home. The lettered list usually goes all the way to P or beyond — including just catching up with distant friends on Zoom, for heaven’s sake. Never mind exercising, meditating, reading good books, taking a walk, doing research for my novel, or reading up on the judges who are up for midterm elections.

My problem is, in the face of that, I all too often feel paralyzed and just read articles, browse Facebook, or watch a video to escape that choking “never enough time” feeling. (Also a feeling that I don’t deserve nice things and shouldn’t get too big for my britches by learning and growing and enjoying life, but that’s another comment for another post.)

Nowadays I’m working on not having that “lack” mindset so much, because it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. Snapping to the “best use of time” (instead of giving into a persecution complex and pouting on the internet) also sounds like a self-fulfilling prophecy, and a much better one. Usually I do have a pretty good idea of what that best use is, or at least I can narrow the list down significantly. I’ll give it a Tuesday try.

This!

It’s not a matter of predicting what action of all possible actions will have the best results. It’s about examining your motivations, specifically filtering out prospective actions that you are inclined to do but know are NOT best.

I think you’ll find this practice does not result in having to consider every single possible action at every moment. You will have inclinations about what to do, but you may also have a sense that you’re being dishonest with yourself about what you should do. We have a natural wisdom for what we should probably do. Go with that, and don’t worry too much about it.

Hmm… I guess I have a different problem then. At any moment I could list off a dozen or more responsibilities that I know that I need to do. Doesn’t matter if I like them or not, they all need to be done, they all are being postponed. And… I have no sense which one is the most important. They all seem equal.

And, sure, some of them have been postponed for so long that at this point “what’s one more day”, so they are the easiest to justify deprioritizing… but that way they never get done until they grow into a crisis, so it’s not a good approach either. Even then, it’s not that they feel less important – it’s just that they are easier to postpone AGAIN.

@vilx I think that is a different problem, with which I can sympathize. I think what’s needed is some life planning to get priorities straight — David Allen’s system or something. Then at least you can establish with yourself certain tasks are definitely more important than others, and reduce some of the indecision.

I have a similar problem with the challenge: When thinking about the morally best thing for humanity and being totally honest, I would have to donate all my money, change my profession (I love it, but there are others that address more urgent needs), and invite a homeless person to live with me. So getting back to my normal life on Wednesday would be interesting…

Even when thinking on a smaller scale it is quite difficult: Should I help my boss get an unpleasant task out of the way or have a conversation with him where I reinforce that I don’t want to work on these kind of task anymore? Should I get some work done, even though I also work on most other days, or go and exercise, which I never do voluntarily.

It’s difficult!

Funnily, I started doing the opposite challenge recently. On Thursdays I’m only doing things I enjoy! (My weekend is on Thursday and Friday.) So any chores, work, things you should be doing, have to wait for at least a day.

An interesting idea for sure David. I’m in as well. This reminds me a lot of many of the ideas James Clear (Atomic Habits) writes about. The idea that positive or negative habits can compound for or against a person or that 1% improvement a day toward a positive habit could equal improvement of 37% in a year. It’s the emphasis on systems (processes that lead to desired results) over goals (desired results). I like the idea of a one day per week system to do the “… wisest and most helpful thing…”. Good luck to us all!

The compounding effect arising our actions is mind-blowing. When you consider how much of an effect a single kind (or nasty) comment can have on your day, and how the results of that day will affect other days (of both yours and others), each action seems so important. With compounding taken into account, small good actions are vastly, vastly, better than the small not-so-good ones. Yet it’s a relatively small adjustment at the source.

I am, just like everyone else, reading this through the filter of my own life experiences and personality. And for me, this brings back horrible memories of growing up very religious and believing that God was inspecting my every thought and action.

Growing up, I believed that thoughts are either good or bad and that actions are either good or bad. And it’s our jobs as humans to eliminate the bad from ourselves and only think and do good.

The consequences were catastrophic for doing/thinking bad things. I could go to hell. I could cause someone else to go to hell. I could be struck with an illness as punishment from God. I could waste my one precious, God-given life on things that didn’t matter and when I die, God would say how VERY DISAPPOINTED he was in me.

During that time, I did a lot of things that my fellow believers praised me for. I was “an amazing kid”, I was constantly taking care of everyone else, and I don’t have to tell you that I was the poster child for anxiety and depression.

This was all a long time ago, and after a lot of observation, I think I have one of those personality types that tends to overdo things. It’s taken a lot of therapy for me to get to a place where I can say “It’s okay to go to bed with dishes in the sink. This is not a reflection on your worth as a person”.

So for me personally, setting a goal of doing the best thing all day would not be helpful. For others, it might be life changing.

I always enjoy reading your articles. You’re a thoughtful person and that shows through in your writing.

I’m glad you brought this up, because it’s an important part of the discussion. These ideas sound religious because they are at the center of our religions. I think they are good ideas, despite all the baggage and abuse that has been heaped on top of them. When you start considering the immense stakes that hinge on our behavior, you can see why people began to take this notion so seriously that they organized their entire cultures around it, and why they would want to drill it into their kids and everyone in society.

However, it’s not the easiest set of ideas to practice and understand. Advocates of these ideas can easily lose sight of what it means to be good, or even never get it in the first place, and end up doing obviously wrong things like threatening children with torture for having the wrong thoughts.

I think the remedy is wisdom — to gain a more mature understanding of how to go about calmly, gently, lovingly doing good and refraining from what you know is not good (I hesitate to use the word evil because of its threatening connotations). Primarily this means understanding it as a practice that you will always fail at to some degree, and that that doesn’t make you bad or doomed.

The idea that God is always watching has been used to abuse people, and that’s terrible. I understand where it comes from though — our actions have consequences on our own lives and those of other people, and no person has to see your transgressions (even you) for that to be true. It’s a little like the weight-loss adage, “even if you don’t count calories, your body does.”

But as you say, how these ideas are communicated ALSO has consequences. To tell people that a vengeful deity is literally reading their private thoughts is untrue in my opinion and unhelpful. But to understand that the thoughts we entertain do have consequences can be helpful if helps you wisely guide yourself through life. The idea of an omnipotent, omniscient deity observing your mind is a model that might help some people really get it, but for others it will make them miserable.

I really like this experiment and the ideas, history, and philosophy behind it. I’m going to join you in doing it. I think it will be incredibly beneficial in helping to cut down on my procrastination. That’s where I find I am not able to be my “best self.” I have a ton of stuff that I want to do – and “should” do for myself and those around me – but I continually put it off for in-the-moment pleasure. And it’s not even pleasure. It’s just not doing those things, which are hard and sometimes scary. They give me anxiety, so I don’t do them. But then my anxiety gets even worse because these things actually really do need to get done at some point and putting them off has only made the situation worse. So this idea, of doing things in the moment, when they are meant to be done, I think will be a game changer for me. I’m really looking forward to it. Thanks, David!

Procrastination is my biggest challenge too, and I know exactly what you mean when you say that putting off work for frivolous pleasure doesn’t even really produce pleasure. It is a miserable, conflicted kind of pleasure.

When you are able to drop the procrastinatory diversion and do the thing you know is right, even if there is anxiety present, the relief from that specific kind of pleasure-misery is palpable, and can motivate you to do it more often.

I’m so ready for this. I’m in. Today will be a practice day. It scares me, which says how much this is what will help me make the leap out of the doldrums.

That’s great Brian. Some practice periods probably make sense, because there is a risk that Tuesday will be such an adjustment you bounce right off, rather than keep up the intention till sundown.

I’m in. Our world, our planetary unrest, seems to be all but screaming for such an internal check and personal endeavor.

I think that’s true. Change comes from inside. That’s a cliche, but it’s a cliche for a reason. In our efforts to improve society we do seem to be too focused on changing others, and it’s not very effective. In fact it’s counterproductive, because it generates a lot of ill will that makes things worse.

Beautiful and compelling as usual. I think the one thing that stops this from being a universally appropriate prescription is that it elides a bit the discernment and life experience necessary to identify the “right” thing. I’m thinking particularly about those of us who fall more on the duty-bound, obsessive side of the spectrum. If I had taken Stoicism a little more seriously in my early adulthood, I probably would have ended up in a contented life, but not the more deeply joyful life I arrived at by letting myself daydream and tune into my feelings a little more.

Yes. There are lots of ways to interpret the idea of the “right” thing. I’m talking about acting from a place of honesty about what you think probably is the best contribution you could make to the moment. Note that obsessing about what to do is not likely to be the best contribution. A way to simplify it is to question your motives for doing something — are you doing it because you actually think it’s right, or just because it’s convenient, or it makes you look good, or some other motive. This doesn’t have to be an elaborate thinking exercise, but just a quick check-in to where this prospective action is coming from, and try to find the inclination that comes from the best place in you. This sense might have to be developed, but I think we all have it.

During the few times I’ve tried this approach in the past, I became both immensely happy and immensely sad. I built up regrets as steadily as accomplishments. Can’t say it was better overall. Can say it was unsustainable for me.

Interesting. Can you say more? What did you regret?

Every use of time requires trade offs. 1 difficult accomplishment can mean leaving 10 or more easy things undone. For example, thinking about and writing this response means I could have been doing something else, and it took some effort to decide which to do.

So there was a period of about 3 or 4 months 10 years ago when I truly tried my best to “do without hesitation the thing that most needs to be done in each moment”. It was often extremely difficult to decide what to do. Usually when considering “the wisest and most helpful thing you can think of in each moment” I fell back on: what would my parents want me to do right now? And I did that.

So basically I cut out all (or nearly all) optional or “time wasting” activities. I discovered those activities kind of fell into 3 categories. 1) the things that I could avoid but decided to do anyway, because they felt like an obligation, such as writing this post. 2) Things I do not find addictive, such as watching mindless TV or alcohol. Those were easy to give up and still are. But then there’s 3) activities I’m addicted to in some way. That’s the kicker.

I found that by giving up 2) and 3), I became intensely and powerfully, but kind of superficially, euphoric. In fact it was kind of uncontrollable, like I was on some “happy medicine” or anti-depressants that I couldn’t stop taking. But at the same time, the addictive activities that I’d given up starting banging inside my head, growing louder and louder, eventually driving me berserk with the pressure of it all. So I realized there was value in bringing balance to my life from the very optional addictive activities, even with the certain downsides that those activities can and do bring. So now I combine the selfish/optional/addictive/”useless” activities in moderation, and overall life is the best it has ever been.

What those selfish/optional/addictive activities are is going to vary from person to person. For me, I need to feel connected by checking Facebook very often, feel connected by reading every opinion article on the Wall Street Journal, feel connected by scrolling (and often commenting) on various online forums, feel centered by reading The Silmarillion for the nth time, feel calm by playing computer or online games of various kinds, not to mention my major coping addiction which I’ll not discuss in a public place like this website.

I guess a lot comes down to a person’s ability to choose wisely what is “the wisest and most helpful thing you can think of in each moment.” If those choices lead to a balanced and full life, that’s great. I personally found that following what “ancient humans say about how to live” (I’ve tried with the Stoics and with Christianity) or what my parents wanted did not achieve that balance. Trying to “Train yourself in each moment to always do the morally best thing” just doesn’t work for me. C’est la moi vie.

@Alan

Thanks for elaborating.

It seems as though your way of deciding the best actions did not actually result in the best actions. So it’s not that it didn’t work, but that the actions you assumed were best were in fact not the best ones. Otherwise it would not have caused so much trouble.

The right action to take has to take into account your limitations and the fact that you are a human, which means you have to maintain decent moods and energy levels and so on. The goal is not to attempt to program yourself as kind of living algorithm optimized for a logical conception of “good.” Taking a more intuition-based, in-the-moment approach to determining the right actions would be more effective (and give you better answers) than a purely logical analysis.

However it is you decide the best action, what makes it “best” is that it fits into an overall pattern that works to make the best life for you and the people around you.

This is exactly how I lived during my mom’s last year of life. She had a grade 4 brain tumour and although she had a surprising amount of good time and little pain (tumour location is everything), it was a very, very challenging year for everyone. But it was also weirdly freeing in that it was extremely clear what the right next action would be in most circumstances. She had a diagnosis and a time limit so we were laser focussed on giving her the best year possible and everything else could fall to the side. I’ve wondered how to recreate this experience, without the terminal illness, and this experiment might just be the thing.

Wow, that’s incredible. I suppose it is the clear sense of purpose that made it so intuitive, because it would let you let everything else go.

I remember when my dad was not well, the whole family made every effort to be there at dinner, and we had such great family dinners and spent a long time talking and laughing afterwards. This seemed to happen automatically and we never had to make it happen in any sense. It was just a natural result of everyone understanding what was important.

I’m in and already judging my motive for getting in!

Very interesting article! The idea you’re proposing reminds me of something I read in Lauren Zander’s “Maybe it’s you”. When we’re really honest, we know deep down what’s the right choice. If you practice listening to your inner voice (according to that book, we have three of them: the brat, the chicken, and the weather reporter), you get better at discerning what is the best thing to do or what you rationalize to be the “sensible” thing at any given moment. For me, the very first thing that pops into my head is usually what needs to be done. And only AFTER that, one of the inner voices chime in and rationalize the easier way out. “Oh, but it rains. You can catch up tomorrow.” And so on and so forth. But I had to practice to witness what’s happening in my own head. I agree with what you’re saying about unloading the mental burden, dissolving the inner tug-of-war. This really brings peace of mind.

I think we do know deep down what’s right. Usually, at least. A lot of people are concerned they will experience analysis paralysis, but I don’t think it’s about analysis, it’s about gently examining your motives, and aligning with this inner wisdom above all else. Different people may perceive this differently — for me the word “voice” isn’t quite right, it’s more of a feeling of relief that I feel when I’m doing the thing I should do. I’m becoming more sensitized to it, to the point where it works almost like a hot-cold compass.

I’m in as well! What an empowering idea!

I’m quite interested in this idea, and especially how people apply it — how big or micro they go, and much they use it for anti-procrastination/“eat the frog first” measures versus larger, morally laden decisions.

Going moment by moment, depending on what judgment mode you use, could hear you stopping to help homeless people and other less fortunate people at the expense of making it to any other activities that day, or never leaving your family’s sad side because you keep realizing anew how much more important they are to you than anything wise.

And both of these somewhat extreme examples could be life-changing and also bring negative consequences depending on what activities lose out.

I realize the spirit of the experiment is likely to not be so open-ended, and start by assuming you’ll obey the lines on the tennis court you’ve set up through prior seeming obligations — show up here, do your job there, spend time with x person, pay for x thing, etc., rather than evaluating all of those against the potential better alternatives that exist in the moments in which they occur.

Or maybe eventually questioning and changing those those structural platitudes and long-assumed vital underpinnings — the obligations your previous cumulative circumstances and life choices have created or seemingly imposed on this particular Tuesday — is really the entire point of living in this mode.

I’m really interested to see how this goes for people and what positive and negatives come from it — and especially any horrible, painful havoc that turns out to be valuable for growth and positive in very important areas later on.

Thank you for suggesting this idea, David.

I’m also curious how people interpret “the thing that most needs to be done,” because how this works does hinge on those interpretations.

The examples you give, like ignoring your job obligations or making your entire day about helping a homeless person, do not seem like wise or productive ways to live. They seem short-sighted and sentimental. Living for the highest good is probably going to involve balancing many concerns, not least of which is maintaining an income and a range of relationships and social roles. Letting all of those connections fester and fall apart for one thing makes no sense and is obviously not the right thing to do.

Good food for thought (and action).

Thank you for not posting this on Tuesday!

I think I have been living this way all my life.

That’s what my father explained to the little me as a main principle in my family.

I hesitated, tried to escape, but slowly it become my style of life.

I turned it to feel pleasure when I di what I have to do and overcome the unpleasant jobs with the pleasure of getting myself the unpleasant jobs.

Now, I am sceptic about it.

It’s like you are driven from outside, by invisible observer, a God…

My kids say that I can’t choose pleasant things to do, because I only see stuff that had to be done.

I think this sense of being driven from outside is the central human spiritual or religious idea — serving something larger and separate from your desires and aversions. There are a lot of ways to conceptualize that structure and the ethos required to live in it — live as though an omnipotent judge is observing, etc. I see how those ideas make sense now as motivators and tools.

I’m the cat in the picture above. Once you barrel down to find what’s REALLY important in life…it can be pretty simple.

Fully agree!

It’s easy to get yourself doing what needs to be done, but how to identify what is the most important among all the to dos?

We are back to resolving at equation re values, Thayer weight and time. And other people’s dependences…

In-ter-est-ing!!!

I’ve recently retired after a lifetime of over-working followed by burnout, and I’m facing questions like, “how many books can I read in a week before it becomes pathological?” and “is organizing the storage closet once again virtuous or another signal that I’m enslaved to late-stage capitalism?”

I’m going to try this, because it sounds like fun, and I’m curious.

As a mom with a big job, I got in the habit of triaging in this way early on. (One hour of TV a week, Thursday nights, as part of relationship management.) It used to drive me crazy when my partner came home from work and settled down on the couch to watch TV or play video games while I started my second shift. Later in life, when my kids grew up and left home, I just kept adding things to my triage feeder: volunteer projects, more freelance gigs. The sense of urgency felt like home. It felt right and virtuous to be overly busy.

Then I got sick, and then I retired.

It’s easy to say I should have made better choices: more rest and exercise, a more helpful partner, less overwork. But I think … I could be wrong … but I think that my training about what it meant to be a mom who was also the primary financial provider to my family and who wants to contribute to making the world better made it too easy to default to working, learning, connecting and service.

I guess what I’m getting at is that for a sizable subset of the population, is it possible that realy reconnecting with ourselves, nature and rest might never feel like the right thing? Another way to say this: What does doing the next right thing look like in the toxic, artificially materialistic social system we live in?

Now I’m thinking about what it means to be healthy and whole, and mostly, doing the next right thing means resting, reading, walking, making and managing feelings of guilt about my own privilege.

I’m very curious about what will emerge for other people, and for me, during this exercise. Thank you, David, as always.

“I guess what I’m getting at is that for a sizable subset of the population, is it possible that realy reconnecting with ourselves, nature and rest might never feel like the right thing? Another way to say this: What does doing the next right thing look like in the toxic, artificially materialistic social system we live in?”

This is a great question. I suppose that what you interpret as the “right thing” is going to depend on your conception of the highest good (i.e. the values you deem the wisest and best to live for). Because I think there’s a distinction between the thing that “feels right” and the “right thing” — the latter incorporates wisdom about what is truly good in the world and the former can be purely a function of basic attraction/aversion motivations. As you know now — and I would guess you knew long before you retired — following instinctual drives alone, in the current social and media environment is not going to lead to fulfillment and meaning, because it is set up to exploit those drives. (e.g. driving consumerism and acquisition over meaning and peace.)

If you genuinely aren’t aware that peace, meaning, and connection to deeper elements of reality are available and more rewarding than satisfying endless material drives, then you would be unable to pursue or even see those things, and therefore “doing what needs to be done” can only feel like running on the hamster wheel. But I think most of us do have some sense that that isn’t enough, and that there are better rewards we can orient our lives and actions towards, regardless of the environment. Developing the skills and insight that allow you pursue those better rewards is what we could call wisdom.

“Because I think there’s a distinction between the thing that “feels right” and the “right thing” — the latter incorporates wisdom about what is truly good in the world and the former can be purely a function of basic attraction/aversion motivations.”

Thank you, David. This is both a freeing distinction and a reminder of the many stories of the spiritual sages, including the Buddha (and Uma Thurman’s father), who left their family responsibilities to seek enlightenment … it’s always comforting to remember that our challenges are old. Not easy, but well-travelled ground. I’m realizing that knowing what’s right next is also committing to live in an ancient question.

I’ve been reflecting on this since I read it yesterday. For a lot of us, ingrained “ought/must/should” messages can make it difficult to identify what is the best thing to choose to do at this moment. The stuff I “ought” to do can loudly overrule what might actually be best for me, for others and for the world. I think, though, that this will sit well with the Ignatian discernment, based on the teachings of St Ignatius of Loyola, by which I try to live. In non-religious, simple terms, this involves asking myself whether a decision (eg what to do next) will be life-giving/energising or deadening/draining. That’s not quite as straightforward as it sounds – right now, deciding to watch a film might feel far more energising than cleaning the house, but how will I feel when I’m living in a chaotic, grubby mess? I’m going to try to apply this Ignatian principle to the Stoicism experiment, and see if the two together will help me focus on what is truly the best activity to undertake at this moment.

It can be difficult to sort out what’s best sometimes. We might have to literally sit down and reflect on an important decision, and there are many philosophical and religious heuristics for that. You can try one out for a while to see how it seems to be serving you. In my experience, the vast majority of cases can be cleared up intuitively, if you get used to honestly asking yourself it this is the right thing or something less than that, based on your current intuitions. Other times you have to reflect on it consciously.

Those impulses of ought/should can come from all sorts of places — both good and bad parenting and teaching, trauma, insight — so they have to be examined. Some rules really are good ones, but the feeling of ought/should itself does not tell you whether it is.

Absolutely. I didn’t intend to suggest that “ought/should/must” are reliable guides, but rather that they tend to be warning flags : when I hear myself use these words, I know that the pull towards this task/ intention needs to be questioned. I completely agree that intuition is a better guide, and I find the question “will this be energising/life-giving or draining/deadening?” helps me get in touch with the deeper intuition.

This is a great idea and I’m definitely in and will be interested to see how everyone else is doing on the experiment page. In the evening, I make a list of the important things I want to accomplish the next day. I’m wondering if this list will be helpful or more of a hindrance for doing what seems right in the moment. I think the list pretty accurately reflects my values- so there’s that. Usually there are a couple of things that get pushed ahead to the next day, or further in some cases (like exercise). I’m thinking I might keep the list and see how it works with this new Tuesday plan

I use a list and I think it’s probably appropriate for most people. There are occasionally times when the right thing is to deviate from the list, but having an overall structure that looks at least initially right is a useful tool.

This article inspired me, thank you for posting it.

Do you have any advice on how to tell what the right thing to do is? Or is it usually self-evident?

In my experience it is often self-evident but not always. The main thing is to ask yourself whether your first impulse is indeed the thing that really needs to be done. That simple question often hints at a more difficult but more responsible action to take that you might otherwise put off or rationalize your way out of.

You don’t always know for sure, but if you don’t know for sure, the right thing is to make an honest guess. The key, whether the answer seems obvious or not, is to be honest about whether you really think it is best or not.

Great pragmatic idea, David!

Perhaps it would also be highly instructive to understand WHY it is we ended up at generally NOT engaging in daily doing the right thing?

A coherent theory of how we got to this point in human history has been proposed, see “The 2 Married Pink Elephants In The Historical Room” at https://www.rolf-hefti.com/covid-19-coronavirus.html

“Separate what you know from what you THINK you know.” — Unknown

I think the general explanation is pretty simple:

Doing the right thing is a new idea. The whole idea of moral good is much, much newer than the evolutionary drives that animate all species. We’re much more deeply driven by our instinctual desire for pleasure and aversion to pain than by any cultural or spiritual insights, because those drives are ten thousand times older than even our oldest ancient wisdom.

Doing good — deviating from instinct in order to create a better life and better world with less suffering — is an incredible human innovation. But it’s new and has to be practiced.

I disagree with you, David.

Rather than that “the general explanation is pretty simple” your general explanation is pretty simplistic, mainstream, and fundamentally flawed, twisted, and erroneous. Is that perhaps why “Turtle Deck” added at the end of his/her comment this? “Separate what you know from what you THINK you know.” — Unknown

The fact is that nearly throughout the entire history of homo sapiens, which began about 400,000 years ago, humans have generally live in egalitarian groups. They were “doing the right thing” such as sharing resources and resisting the accumulation of wealth, etc.

It means your claim that “doing the right thing is a new idea” is false. “Doing good” HAD BEEN generally practiced by humans for hundreds of thousands of years. But then it generally stopped about 12 millennia ago, all the way to today. Why?

“Turtle Deck’s” mentioned article on the theory of the 2 married pink elephants does offer an interesting cogent factual explanation.

@Jean-Marc

This is actually a deep and nuanced philosophical discussion, but I will try to explain what I mean briefly.

At some point, hominids discovered the ability to deviate from instinct, which allowed them to engage in egalitarian behavior such as renouncing things they desire for the sake of others, or moving into pain and difficulty despite the instinct to avoid it. They became able to depart from the axis of approach/avoid and instead move along an axis you could call good and evil, for lack of better terms.

How long ago that happened is debatable, but I didn’t put a date on it. It may have been 400,000 years ago as you say. But that’s still at the far tail end of our development, which began closer to 4 billion years ago. Approach/avoid has been entrenched in life since way before we were human or mammalian or even vertibrates. Instinct is sooooo much older than good/evil. On this timescale, 400,000 years *IS* new.

After tens or hundreds of thousands of years of humans experimenting with altruism and other deviations from instinct, they began to consciously philosophize about how it works. They came up with ethics and wrote them down. Very recent incarnations of this include Buddhism, Christianity, Stoicism, etc. It’s been a long road.

I’m glad you put in that final paragraph. I’ve known for years this sort of approach is the right one, but have yet to overcome serious executive dysfunction to give it a go. I’ll schedule a day in my calendar and give this experiment a go. Good luck to all of us!

Just notice what happens when you have even a single victory over the impulse not to bother. There’s something transcendent about it. And it really only takes a moment to do the right thing, so it’s not a matter of bearing some huge load all day. Best of luck.

I am in. Practice the practice. A day without letting myself be distracted from what I should be doing sounds very peaceful although a bit daunting!

Daunting is good! It awakens new qualities in us.

This sounds very interesting and I’m inclined to try it with you. However, it seems to be based on a premise that I’m skeptical about: that we, at all times, know what the right thing to do is. Can’t everything be rationalized to be the right thing? Especially indulgences. I had a really rough day, I’m gonna treat myself with some fast food and a Netflix evening. And it wouldn’t even be wrong. Instantly gratifying actions are good for our well-being, even if usually only in the short term. Or what about conflicting goals? Spend an hour working on a critical project or play board games with your family? Neither of these options are inherently good or bad, it’s a matter of prioritization.

Maybe you, David, have a strong intuition about the right or wrong actions and therefore wouldn’t end up in this dilemma. But I wonder if there are differences between individuals. Im not saying this is a stable trait, but something that needs to be learned, practiced and cultivated.

It is definitely something that has to be practiced and cultivated. But I think we know the right thing more often than we give ourselves credit for.

Don’t worry about doing the absolutely morally optimal thing. The point is to recognize more and more instances in which you knowingly do the not-best thing. In those clear instances, make a better choice.

You might notice a certain feeling that comes with doing the right thing despite its difficulty, especially when you were considering not doing it. There is a liberating, unconflicted quality to it. Once you have a taste for that quality, you can use its presence or absence (or its opposite, conflictedness and guilt) as a sort of compass to navigate by.

I’m in today! Tried to do a test run on Sunday – did not go well. So I’m here because the best thing at this moment in my mind was to check in here and make a sort of public commitment to this experiment to keep this at the forefront of my mind – a mind that has become mush in the past year. It’s brain fog, likely covid related and definitely exacerbated by extreme stress, resulting in the worst ADD/OCD I have ever experienced – or maybe it’s something worse but I’m not going there. This idea is so simple but like many simple things, not easy. Or maybe it is. Either way, this was a well-timed idea/challenge for me. Committing and recommitting to the “best thing” today brings inspiration and hope that I can wrangle my brain back into the corral of my choosing at any given moment.

Hello David,

Yesterday i was superwoman…. That person i have been struggling to be for years. A perfect wife, friend, mother, housewife. It was so easy to do actually. There were moments when limiting thoughts came to me to tempt me to give up and do some time wasting but it was surprisingly easy to override because i had made the pact that i would do this for this tuesday. The fact that it was just one day helped me to stay strong: Seeing this made me realise that motivation/willpower/self discipline is not this huge thing that is imposible to overcome. You have just a tiny moment that you push through then the its over and you are on the otherside where things are easy because you have started. The wall seems to get gigantic when i stop and think and look at it etc….

My day in brief…

got up at five

shower(washed shower down at same time) finished by cold water to wake me up

dressed and makeup.

meditation

journal morning pages

gratitudes

smoothie

water and vitamines

started cooking

washing in and down

walked

saw a friend

Cleaned lots

night routine… clear up, washing, shined the sink

bed at 10

BRAVO ANNA!!! :-)

It was an easy day though because i had my best friend and her family over to eat because its a national holiday here in France.

Unfortunately today (the day after) was like a hangover after a drug binge. I wasted a lot of time surfing, got minimum stuff done. Did manage a guided meditation but i quickly forgot the message i learnt. Had a raging argument with my middle child and i just felt really crap about myself.

Im looking forward to next Tuesday.

Im pretty sure i couldnt keep it up every day but maybe parts of it will leak into the other days of the week like the meditation i did the day after.

Thank you for this experiment!!

Anna

Wow, amazing. My day was similar in the sense that I just went from one thing to the next, pushing through those moments of doubt and temptation, which were occasional and small, and felt great by the time I went to sleep.

I also experienced a kind of “hangover” the next day, which I wrote about on the experiment page. I want to learn what that’s about and how to manage it.

David,

Psychologists have wrestled with this question a lot. You can find some of their answers under topics like “executive control” and “ego depletion.”

The hangover effects you’ve discussed are common.

The incredible pushback you’ve got on this suggestion is, itself, probably a great indicator of another article that needs to be written some day.

For me all the objections to your main point have one thing in common; they’re all symptomatic of overload. I lived that way for a long time too. Didn’t like it much. It’s the hallmark of ADHD types; we’re exquisitely responsive to external cues, which often means a life spent trying to accomplish everything for everyone, and rarely accomplishing anything for anyone as a result.

For me that life basically meant a world where I was driven by a cycle of fear and recovery.

Haven’t finished reading. Just had to say that I’m already doing something similar to this! Incredible how brains converge on similar ideas. No surprise, considering how much you’ve shaped my thinking

Anyway I’ve been at it for ~3 days and it’s insane how much self-control and productivity I have when I refuse to see past the next step. This perspective shift is so effective, I think, because it forces us NOT to think about the past or future

It sure does bring your mind back to where it’s most useful, which is on the task at hand, not haphazardly thinking about the future. And of course there’s always a task at hand, which strangely comes as a kind of relief. There’s so much less uncertainty.

I remember when you wrote about this thinking last year and it certainly sparked my intreasted, given my intreast in Stoicism was also high at the time, it’s something i’ve been thinking about a little bit ever since.

I’ve been struggling with feeling overwhelmed, confused, lost and constantly trying to figure out what I need to do, how I need to think, what I need to change in myself, how I can do something awesome, how I can be awesome, because I just seem to be stuck and suck at stuff and it’s all so draining and overwhelming.

So i’m trying to really apply this, I think in some ways some of us that function simular to how I do, have lost this sense of being, I think a lot of people just kinda go along with everything and do this automatically, those of us that like to think about things, run the risk of losing this way of being, getting stuck within our thoughts and kinda saying to the natural process of life, that we somehow know better.

So we get stuck and bogged down in our thinking, trying to make sense of it all and figure it out, but really all we can ever do is do something in the moment and then the next moment after that, so I feel like if we are able to achieve what you are describing, it’s almost a shortcut to that process, it allows us to side step all this over thinking.

I think that is what people that are good at planning have right, the planning allows them to believe they know what is going on, so they can take the next step and just do what needs to be done then adjust on the way. I always try hard to organize and plan, but I am terrible at it, it’s too difficult to decide things, or figure them out, there are too many variables and options, but really the key is just to do things, to do the next most necessary thing, then the next, a ‘fake’ plan allows you to do this, for those of us that suck at planning, the problem is we think the plan has to be real.

A fact that blew my mind recently was the idea that half way through a chess game there are more known moves than that of the atoms in the universe, this is why logic and over thinking quickly fails you, no matter how smart you are, the world is crazy complex and anything can happen at any time, if chess, which has a small board and a few very clear and defined rules can be this complex, then no wonder we struggle when we try and figure life out.

It’s perhaps then not something to be figured out, but something to experience, a wild ride, we are at a theme park, we get to choose what rides to go on, but from then on, what we do is ride them and see what experiences they bring.

Funny thing is, I’ve been reading Raptitude over ten years, I just never actually subscribed cause I like to keep my inbox low, so I’m usually a little late to see new posts.

Last week right around the time this was posted, I had the exact same idea, except in my version, instead of one day, it was fifteen minutes. (I try to set realistic standards.) If I really try it I might come back here and report how it went.

The first Tuesday I did one thing and it was an important thing. This past Tuesday I did another important thing. The energy of the experiment has helped me to get other things done as well. One big problem was solved that had been out there for a while. I thing the solution came in large part by just moving the energy around the things that had been sitting and collecting lots of dust ! Thanks.

I tried this last Monday and I will try it again tomorrow. The most enlightening thing was how similar a Stoic Monday was from a typical Monday. I got plenty of work done, but I also allowed myself a half hour of YouTube after completing a certain amount of work I have scheduled for myself every day. I even spent the evening curled up on the couch watching two episodes of Gravity Falls with my husband. Neither of those things are productive, but both were the best decision for my time. There were a few changes from a typical Monday: I got way more work done on my book and I didn’t check social media once.

That’s what I have noticed: it results in a good day’s work, but not a superhuman day’s work, and certain things drop out completely because we always feel conflicted about them.

I believe your post has a lot to do with trusting oneself. While I’m prepared to deal with the ambiguity, the one thing that deters me is the ‘being’ that precedes the ‘doing’. What I mean is that ‘doing’ the right thing even if you don’t want to do it becomes easier when there’s mental reluctance or physical pain associated with it. However, this ‘doing’ becomes so much more difficult when there’s emotional vulnerability attached to the action. These will be the times when I’m not sure I’ll be honest with myself. Any thoughts?

There is a trust (or faith) element here, for sure. Once you recognize the “rightness” of that course of action, it still takes a certain kind of courage to move your body into the action itself, despite the physical or emotional discomfort of that. In my experience, it doesn’t take long before that resistance dissipates, because something about the mind recognizes that the reluctance is what’s painful, and you’re freeing yourself from it by acting in the best manner possible anyway. However, before that moment of reversal, you have to have a certain kind of faith or self-trust in the idea that such a thing is possible and that it is better than not doing it. The more often you do, the easier it is to find that trust.

I love this one. I may even quote you in my next book. If I do I’ll send you a copy!

Comments on this entry are closed.