The first thing every human learns about politics is that there are things you can say that will make people hate you, and things you can say that will make people approve of you.

What those things are depend on the beliefs of the people around you, which depend mostly on where and when you grow up. Say aloud that you think thieves should go to jail forever, and in some places your peers will agree with you and make you feel good and normal, and in other places they will call you a horrible person and whisper about you at the other lunch table.

The same thing happens with every politically-tinged belief you utter, even before you even know politics is a thing. If you suggest that hunting for sport is wrong, visible tattoos are a reckless life choice, conscientious people don’t drive SUVs, or church teaches people to live moral lives, you’ll get either approval or pushback, depending on who’s around.

You learn quickly what the others want to hear and what they don’t, ingraining within you a sense that some of your thoughts make you worthy of acceptance, and some make you contemptible.

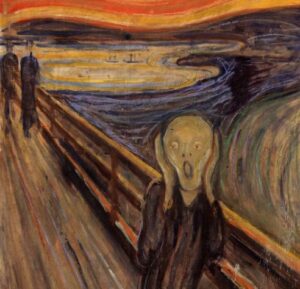

Our motivation to stay on the good side of the tribe is deep, deep, deep. Prehistoric. Prehuman even. We really don’t want the other humans to kick us out of the club. Just as our survival instincts draw us powerfully towards foods that are high in fat and sugar, and low in bitter toxins or smelly pathogens, we’re also drawn towards the speech and social behaviors that will keep us in the good books with others. We learn to sniff out which ideas are sources of social nourishment in our world, and which are social poison.

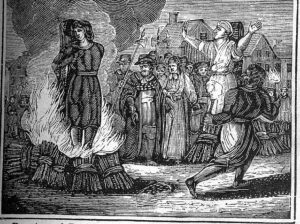

Over the years, it will be drilled into you what you can and can’t say if you’re going to be accepted. You know you can’t tell them you enjoy picking your nose, even if you do. When you unwrap a birthday gift, you’re allowed to say that you like it, but not that you don’t like it. From our first years of life, we’re subjected to this ongoing process of Pavlovian conditioning, in which you get burned for saying certain kinds of things, and loved for saying certain other kinds of things. You learn which buttons deliver the pellet of food and which deliver the electric shock.

Like any trained animal, the reinforced behavior becomes less conscious and more reflexive over time. You gain an intuitive sense how to move deftly through the maze without getting zapped, thinking less and less about how you’re navigating it at all.

Most political beliefs are about feeling safe

It is inevitable that you will inherit a political worldview this way, and it will happen long before you even know this adult word “politics.” By the time you’re a teenager, certain ideas, symbols, names, and concepts already have a long history of making you feel worthy of inclusion in polite society, while others feel like dangerous heresies.

Here’s the problem though: this Pavlovian mechanism delivers its rewards and punishments regardless of the truth of what is said. A viewpoint doesn’t need to be true, or even coherent, to be the predominant one in your world. What’s popular and what’s right might overlap, but they’re not the same thing. If everyone around you insisted the world was flat, you’d be accepted whenever you said so, and made to feel like a complete loser when you said it was round, regardless of the true shape of the earth.

Growing up in such an environment, telling people you think the world is round would make for an unpleasant existence. In fact, it would be scary to truly entertain the notion in the first place. If you believe the world is round, you’re an outcast. Your classmates don’t talk to you and your family is embarrassed of you. If it’s flat, you belong and you’re okay. Which worldview is going to feel like the “right” one?

Because this Pavlovian speech and thought training happens from toddlerhood on, you learn the “right” way to think many years before you’re capable of carefully thinking through a complex aspect of the adult political world. A nine year old can see which behaviors celebrities are praised and criticized for, who their parents make jokes about, and what their teachers seem to think is wrong about the world, but not be able to understand serious, informed arguments for or against immigration, recreational drug use, or affirmative action, let alone more abstract ideas like capitalism or socialism.

In other words, we learn the political valence of ideas — whether those ideas make a person “good” or “bad” in our local world — long before we have any functional understanding of the ideas themselves. You come to know the color, the taste of a belief, before you learn where it came from and why it persists in society, if you ever do.

The Affirmation Trap

Surely though, we do get around to that rational and informed thinking, right? Everybody carefully re-examines their inherited political leanings right when they turn eighteen, before ever casting a vote or lecturing their Instagram followers about law enforcement policy.

Let’s just say that’s probably unusual. The Pavlovian reinforcement machine never stops, and there often aren’t a lot of incentives to reconsider what already feels right to you. You’re surrounded by peers and media sources that either tell you you’re absolutely right, or imply that you’re a deplorable idiot. Open debate doesn’t often go very deep before people get mad and stop debating. Unless you have a novel experience that makes continued belief impossible — you travel to space and look back at a spherical earth — your inherited worldview continues to feel right by default, like home cooking feels right. Like being loved feels right.

However right a belief feels, though, chances are its internal logic and factual basis have never been tested, because that takes a fair bit of work, and an elective project of proving yourself wrong isn’t very attractive to our affirmation-seeking brains.

Besides, you’re a reasonably smart and well-informed adult, right?

Sure, but so are a lot of people that completely disagree with you. The conventional explanation for why people vehemently disagree with us on political issues is that those people are stupid and bad. Maybe they are, but that assumption seems like a bit of a crutch, considering that many people undoubtedly think that about you.

Either way, how do you know?

Letting go of the life raft

If you want to get to the bottom of some disagreement, or closer to the bottom, you have to do something fairly terrifying: you have to entertain the possibility that what’s commonly known as “wrong” in your world might actually be right, or at least sensible, and find the best available arguments for that. To honestly consider those arguments, you have to identify with people you’ve been perpetually trained never to identify with, under threat of losing your status as a good and worthy person.

It’s a battle against instinct, like turning down food when you’re hungry, or jumping out of a plane. Just try reading think-pieces from the less-comforting side of the political spectrum, whichever side that is for you, with the intention of really getting where they’re coming from. If you’re unused to doing this, it feels physically and emotionally unpleasant. Fight or flight kicks in. You feel the anxiety of flirting with ostracization — echoes of the birthday party you were conspicuously not invited to, the look of disappointment from your father, the feeling of walking into a room and realizing they were talking about you. Terrifying stuff for anyone.

Despite the moral nausea it can induce, I maintain that this can be a thrilling and liberating exercise for an inquisitive person. You consciously try on an unfamiliar thinking cap, borrowed from a columnist or famous philosopher, and wear it while pondering one of the issues of the day, all while staying aware of your reflexive tendency to launch back into your default, inherited worldview.

Much of what you read you won’t be able to find a place in your heart for, but almost always, there’s something. A glint of an ignored truth. A shared fear. A new sympathy.

Most people will never do this, but you could. You can let go of the “what’s right is what everyone says is right” life raft, and explore the whole ocean.

I’ll try to give you a reason to do this aside from, “It’s interesting.”

The Fox and the Goose

There’s a clip from the BBC’s Planet Earth series, in which a fox is trying to steal adorable goose babies while the mother geese desperately try to fight it off. The viewer is almost helpless but to identify with the geese. But then they show the fox bringing her catch back to a den of seven adorable baby foxes, who must share the small amount of food their mother was able to find today. Now the murderous fox is also a tireless working mother, doing all she can to keep her pups alive.

This moment, in which you see both of these realities at once, is analogous to what happens when you explore an opposing political stance in good faith. The other side — the side that hasn’t been trained into you your whole life — seems wrong, wrong, wrong, until you achieve a sympathetic view of their predicament, and hold it in your mind at the same time as the predicament centered in your habitual, inherited view.

In these moments, the world starts to make more sense. If you can achieve a multi-viewpoint understanding of the debates over gun ownership, law enforcement, socialism, capitalism, transgenderism, housing policy — even if you still adamantly favor one position afterward — the conflict no longer needs to be attributed to malice or stupidity on the part of half the population. There’s a better explanation, which is that contentious issues tend to be multi-faceted and morally complex, and people fixate on the first facet of an issue that makes them feel something. To make it worse, our culture incentivizes the denial of moral complexity. Simply put, it’s easy to motivate people with simple moral stories (those guys are bad) and hard to motivate them otherwise.

Once you start to appreciate moral complexity, and the way that even one complex issue can scatter a population of decent people into opposing camps, it makes less sense to hate people over disagreements. If you yourself can achieve multiple sensible viewpoints on a given issue, so can a population.

You might discover that you carry a lot of fundamentalist beliefs — group X is always the victim or always the perpetrator; people who want Y only want it for reason Z — and that these sorts of one-note beliefs explain very little about the world, and create enormous amounts of unhappiness, not to mention bad policy.

This doesn’t mean all views are morally equivalent. Some are predicated on demonstrably untrue claims, some use circular logic, some equate things that shouldn’t be equated. The point of exploring beliefs you don’t already identify with is to figure all that out — to finally begin to assess the viewpoints on offer by their merits and faults, and not by how they taste, or how fashionable they are.

***

Photos by Toa Heftiba, Imants Kaziļuns, Mullica, Aaron Burden, Nerfee Merandilla, Edvard Munch, NEOM, Sachin Khadka, and Eric McLean

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

Do unto others as you would have done unto you.

Works well every time for me.

I don’t disagree, but how does this rule inform specific political beliefs (i.e. free markets vs redistribution, strong vs lax drug laws, etc.)? I know it works well enough for interpersonal relationships, but if we’re talking about how society should run, it doesn’t really get into the details. Does “do unto others” suggest capitalism or socialism, for example, and how do you know which?

Political beliefs is the term used by a group of people attempting to do something. Capitalism is the word for a person who raises eggs and needs lumber approaching a tree cutter and asking how many eggs would he trade per board. They agree on a number and both needs are met. (Government, when it functions correctly, is there to handcuff greed in its myriad of ways). Redistribution is the term for taking from one and giving it to another. There is a fine line between helping someone who cannot help themselves and actually doing it for them. That’s why charities have always worked so well in the past because they knew who needed help and who wanted a hand out. We cannot escape from evil here on earth. But we can live very well if we ALL practiced love, kindness, generosity and forgiveness…virtues that should be reinforced in any great society.

I think there can be times where that doesn’t really work. For example, imagine you have Person A and Person B:

Person A finds that when they’re going through grief or stress, they do best when they’re left alone to work through their feelings privately, and that it adds to their stress when other people continually reach out to ask if they’re okay, if they need anything, etc – they feel pressured into spending emotional energy engaging with other people when they don’t have any to spare, and guilty about rejecting unhelpful “help”. They feel supported when other people are understanding that they need space, and let them reach out when they’re ready.

Person B finds that when they’re going through grief or stress, they do best when other people reach out to them periodically, and check in about how they’re doing, and if they need anything, and so on – they feel uncared for when other people keep their distance and wait for them to reach out, and too drained or guilty to “demand” other people’s attention and/or sympathy. They feel supported when other people make sure they know they’re in people’s thoughts and hearts.

If Person A and Person B treat each other how they themselves want to be treated, they’ll each be doing the wrong thing for each other.

I think instead, it makes more sense to ask other people how they want to be treated, and then do that – even if it’s the opposite of how I would want to be treated in the same situation.

(Although I guess you could say that on some level, I actually am treating people how I’d want to be treated – I want to be asked how I want to be treated! )

Such a good article – thank you. It takes work not to go to knee-jerk but it also keeps us separate from other humans who care about so many of the same things – our family, peace in the world, an ability to feel self-determined in the social context of our lives. And often even a little reframing can help – blood-thirsty fox or devoted mother? Hmmm…. curiosity can help.

Curiosity kind of has to be a driving force. There has to be some level of interest in other ways something may be thought about. It can be cathartic to find a perspective that seems to explain more than your old one.

It’s getting harder and harder to find people willing to be nuanced, open-minded or heterodox in their beliefs due to the balkanization of public discourse through the media’s need to capture an audience and big tech’s algorithms. We’re drifting back into the radicalized ideological tribalism of the 1930s due to a lack of intellectual courage and good-faith discourse. Thanks for the push back.

excellently stated, thank you. I work with myself and my friends on this all the time! thanks for the insight.

I think we might have reached a point where it’s getting easier again. The problem has become bad enough that it’s obvious to enough people that open discussion is vital to prevent a repeat of the ideological extremism that blew up the 20th century. There’s been a weird suspicion of free speech (strangely coming from the left) that I like to think has peaked, as more and more people see how toxic it is. The heterodox are out there for sure.

Based on surveys, demographics and sociological studies, the myth that the emergent suspicion of free speech along with cancel culture is coming from the left isn’t evidence based. The phenomenon cuts across the political spectrum (with individuals identifying as right of center actually favoring censorship a tiny bit more than those on the left).

I hope you’re right about the phenomena having peaked and that people are becoming more interested in truth seeking and being involved in open dialogue with others who hold different perspectives. However, this phenomenon mostly appears to be a generational shift that started with Millennials and has accelerated with Gen Z — based on Jean Twenge’s recent book “generations: …” (a major contribution in the field as opposed to the usual pseudo science that passes as research on generations in the media).

While I find the generational shift towards censorship alarming, strangely (as it appears to be contradictory) there is also a generational shift towards inclusivity, which I find encouraging.

I doubt that but I mention the left specifically because they’ve tended to be the ones defending free speech during my lifetime. I expect conservatives to be more authoritarian about speech — when the left is doing it too we’re in trouble.

Or the platinum rule: do unto others as they would have done unto them.

I understand about the differing view points and where one stands on believing things. In politics, now for the most part, is what is “harming” people. I am a very open minded person and able to listen to others but when what you believe actually harms others it’s wrong. Maybe this isn’t where you were going with this but it’s what kept creeping into my mind…plus I don’t think most politicians are actually “believing” what they are saying but just trying to win for the money or whatever benefits them. Maybe they do..that’s scary…caring for others should always be the “in” thing.

i think that’s the crux of this article, that people of a different opinon do not think that what they believe is hurting people, or they very sincerely believe that what you believe is hurting people. it really is a helpful exercise (though uncomfortable) to do as david suggests ….

i’ll take on very hot topic to demonstrate. let me be clear i am VERY pro choice, anti forced birth. but i have seen first hand the panic abortion inspires in people who truly believe it’s murder. it’s not going to change my mind, but trying to put myself in their position culturally, religiously, etc. i can appreciate how to talk to the more open minded among them. and vice versa, those (admittedly few) who have the patience to sit with me and understand where i come from in good faith are way less likely to be the ones engaging in radicalized domestic terrorist activity like killing doctors.

this is nothing to say about the shameful politicians who use it as a talking point while masking their actual beliefs or practice. those folks can go jump off a bridge

Agreed, but the point is that people fixate on one kind of harm (or benefit) and do not think about other, perhaps unintended harms or benefits. That’s what you learn from reading multiple views on the same issue. For example, many people think “harmful” speech should be curtailed, but curtailing speech creates other harms, such as giving the ruling class more power to marginalize groups it considers undesirable. It is always more complex than “Does X cause harm or not,” because anyone can identify harms from virtually any policy.

The job of a politician is to sell policy to the public, and they tend to frame it in the most simplistic manner possible.

Yes, listening to an opinion you know you don’t like, but pretending to be on the side that DOES like this view, is a great way to broaden one’s understanding.

I love this insight in your essay, David:

“…people fixate on the first facet of an issue that makes them feel something.”

Fantastic piece, David. During the pandemic and maybe even a bit before I went through this exercise repeatedly. It IS uncomfortable, and unpleasant but it is so valuable and necessary. Literally pretend you believe the “other side” and you can begin to see things you realize you ignored because it didn’t fit your narrative. Politicians and the powerful will always use our emotional bias to divide us and keep us busy fighting the straw man.

The pandemic really got me going on this. The claims made by both main narratives were so absurd I really had to let them both go and try to figure out what’s happening without deferring to a camp. This was liberating, to drop the feeling of having a “team” and scrutinize everything I heard.

Well-crafted David. You are so right that it’s always better to be informed on both sides of an issue instead of merely opinionated on one side.

I suggest everyone watch the documentary Accidental Courtesy about R&B musician Daryl Davis. He puts into practice what David is touching on here.

By simply giving KKK members space to explain their beliefs, Daryl is able to calmly discuss racism in an open forum and let them decide if it’s right to continue in the clan.

Watch. The results are inspiring.

I’d like to see that doc. I think it’s better to hear out the bad ideas. If you play the “free speech, but only for ideas I approve of” card, not only do you undermine free speech as a right for yourself, but suppressed groups will only feel more justified in everything they do, including violating laws. If you say, “Okay, let’s hear it — how do you think society should work?” then they have to defend their ideas openly, and everyone can see how much/little is really there.

I would add that free speech does not mean no opposition. I think the value of an actual debate is huge. The value of a skilled interviewer is also huge.

@Tim:

Agreed, and I think that’s a point that is being deliberately obscured by some. Defending free speech for bad ideas too is being conflated with defending bad ideas.

Steve, the one part of what you say that I disagree with is simply the “both sides” aspect. There are far more than two sides!

I’m a high school teacher one exercise of critical thinking I recommend to students is simply this: make sure that you can name people, where, though you disagree with their conclusions, you respect their thinking. Also recognize people where, even though you ultimately agree, you can recognize the weaknesses in their thinking.

This is really the distinction that needs to be made. What is said needs to be evaluated — knowing their political stripe isn’t enough to evaluate it.

You may already be aware of this, but it’s worth saying for anyone who is not: what you are describing is the _neurotypical_ process of socialization. This experience is “normal” but it’s very far from universal.

One of the classic markers of neurodivergence is an inability to naviagate this at a young age. Most of us NDs figure this out as adults, if we ever do.

I was thinking about this as I was writing it but didn’t mention it. Social cues vary in subtlety and some people are more able to understand them than others.

Nobody escapes the corrective feedback on what they say though. How efficiently it is integrated will vary.

This is exactly where I’m at at the moment! I am at the stage where I can feel myself being swayed to the opposite beliefs that I’ve always had but even on the other side I’m thinking… This might not be totally true either. It feels exciting and scary and uncomfortable and easy and difficult. I can feel myself trying to make the opposite view my new group or religion but I’m learning to then question this new view… Kind of swaying back and forth. I never got a tattoo because I didn’t want to join the religion of tattooed people. Everything becomes very quickly a sort of religion…. I was a vegan from birth until 25 then started eating meat because I realised it had become a religion in my head. I had fallen in love with a farmer that had 150 cows he reared to sell for their meat. Veganism was stopping me from marrying him because of this. Now I eat very little meat. I still feel bad though because three of my 7 siblings are in the vegan religion. Meat is murder in their view.. Mine too but with politics and everything really I’m trying to not go with what would ideally be the right thing but accept that as a mass and biologically people will earn more money than the rest, people will eat meat… I’m not good at explaining but right now I’m trying to start from the standpoint of reality… Humans are and always will be and are like this and work with that rather than try and change everyone to an ideal.

Oops I wrote my surname instead of my name on my last post it was Anna writing.

Changed it for you

I totally relate to your comment. It is very strange to stop officially identifying with a side. It is liberating to not have to defend ideas your “side” wxtolls that you know have holes in them, but then you find yourself bouncing on to other ideas across the asile, which also have problems. I think it’s best to break any clinging to any worldview the best you can, but be aware that we have a strong tendency to cling to a political identity.

Do you not think that people can claim a political side simply because that side best supports their moral beliefs and not because they want a “team” to belong to?

@Phil — If you’re identified with a side — as in, you reflexively come to the defence of the “left” or “right” position when it is criticized, without looking into the specific issue — then you are supporting that side out of a kind of emotional loyalty rather than the result of honest reflection. In my experience, it is the norm to espouse strong opinions about things they have barely looked into personally.

Regarding defence of a position – that depends on the circumstances. One doesn’t necessarily need a deep understanding of an issue to counter another’s perspective if the argumentation itself is flawed.

I identify with the left because it’s political philosophy best suits my personal values on most issues, and they are most likely to implement policy that is in line with my moral beliefs. I oppose the right because I believe their political positions are regressive, harmful and lacking in rigor, or outright hateful at worst. Your issue seems to be epistemological, which in and of itself is valid, but the way you’ve attached it to identifying with specific political sides seems odd to me. It gives the impression that doing so necessarily entails reflexive thinking. But that doesn’t follow. A person could be considered politically radical and still be a better critical thinker than someone who doesn’t “identify” with any side. I may be misunderstanding you, though. Its also worth noting that identifying with a side doesn’t entail that you agree with every position within it, or that you believe that the movement doesn’t have issues that need to be corrected.

I think it’s worth mentioning that political affiliations are often more complex than simply left or right. Within the left, you have anarchists, social democrats, left-leaning liberals, socialists, Marxists and non-Marxists, etc. And in my experience, there’s often a good deal of disagreement between and within these groups on certain issues, or at least how best to approach them.

Nowadays everything seems religion, meat eating, veganism, driving a car, driving bicycle, cat or dog. Better would be, that those examples be choices with expanation (to self) why I’m doing this but not that. Saying that some things are religion is locking their mind and don’t see variable options available. If Spock would be real person, he would say classic “Highly Illogical” when watching our actions globally.

This is a good and worthwhile article, but you make one big mistake based on something that you were programmed to do from the time you were a very small child: to be a nice guy. We’re in a very unique era right now, according to the 6,000 climate scientists who worked on the IPCC report, and almost every scientist from every other scientific discipline in the world, because the science in the IPCC report makes perfect sense to ANY scientist. So now we live in a world where we have less than a decade to ameliorate global warming, and that’s the best case scenario. It’s very likely that it’s completely too late. But there has never been a time when certain issues have been so clearly FACTUAL, and NOT a matter of opinion, and NOT left or right, Republican or Democrat.

Look at the string of the presidents we’ve had throughout our lives. And look at our federal representatives. I’m 69, and for all my life the vast majority of our representatives and presidents have LOVED the military-industrial complex, and they have done the bidding of corporations. Like Chris Hedges says, sometime during Bill Clinton’s presidency, Democrats became Republicans and Republicans became insane, and meaningful legislation became impossible. That’s where we’re at right now.

You can plot it on a graph: moderate presidents, whether Obama or Trump, steadily and continually increase carbon emissions into the atmosphere. 2023 will be the year of the largest amount of carbon emitted in human history. That trend is so solid and so steady, it’s pretty fair to say that it’s a fact that voting for a another “moderate” like Klobuchar, Buttigieg, or O’Rourke, all of whom promised NOT to provide universal healthcare, is just a slower form of mass suicide than voting for a Fascist (Republican) like Trump or DeSantis. A moderate like Biden, whose main campaign promise was that he wouldn’t fundamentally change anything, is a force for slow suicide, for example, look at his huge oil lease in the Gulf of Mexico and his gigantic oil drilling project in the pristine Alaskan arctic, which he promised he would “never, never, never” do. Look at our military budget. And look at the fact that 65% of Americans are living in actual desperation.

The far left can be idiotic and embarrassing about emotional hot-button issues, like having 4 different kinds of color-coded bathrooms, and making everybody state their pronouns, but those people are outliers, and generally the left wants to address the environmental catastrophes and the homeless problem and the 2 million Americans kept in cages, insane military spending and constant war crimes, and all of the other issues that are destroying and impoverishing our country, while laundering our tax money into the pockets of military contractors, the healthcare protection racket, big pharma, big oil, etc.

One of the sickening things about TIME magazine is how polite they are in pretending to discuss both sides of an issue, while ALWAYS bending the overall thrust of the article to the side of the multibillionaires. TIME has LOVED every fake war America has fought since WW2. Your article urges listening to both sides, and to oversimplify a bit, you are telling us we’re supposed to read the literature and watch the videos put out by flat-Earthers, and to do so with an open mind, even though their actions and their votes are LITERALLY destroying the lives of our children and grandchildren.

The fox and the goose story is a great example of the good that comes from seeing things with an open mind. There are still, of course, many issues where there are all kinds of gray areas. Personally, I check out a lot of conservative information daily, and you’re right about there being glints of truth in it.

From the age of 18 I’ve trained myself to see things through the eyes of an extraterrestrial scientist/sociologist. It’s a simple thought experiment. An alien would think internal-combustion-engine gasoline-powered cars should have been in a museum 30 years ago, dangerous, polluting Rube Goldberg machines that are pushing the world to war (remember Iraq and Afghanistan and Libya?) and raising global warming to a level that will likely end human civilization.

An alien would think America’s proxy war in Ukraine, destroying the whole country, traumatizing most of its children, killing most of its men, and literally playing Russian roulette DAILY with the chance of global nuclear holocaust, was as absurd as fire departments from different districts having a fistfight outside of a burning apartment building full of people! We don’t have a MINUTE for the Ukraine proxy war, all to see which set of corrupt oligarchs get to govern Crimea, Ukrainian ones or Russian ones.

I hope all your readers will find and read my comment AND follow your good advice about how to read it. Have you noticed that the crazy mass-scale brainwashing has been so effective this time that even strong, ethical progressives, who have never been fooled since Vietnam, are rooting for Biden to hurry up and send some F-16’s to Ukraine?

I don’t want to argue any of the specific claims about climate and foreign policy you make in this comment although I do agree with some of them. More importantly I agree with you that believing one side of the spectrum as being substantially right on everything is the biggest mistake of all. You have to examine each question yourself and reject binary identification.

About the “outliers” on the left — I agree with you that it is a minority of the left that has gone insane, and that most of us want sensible policy without the drama. However, two points: (1) minority ideologies can wield outsized power over culture and policy, and they do — we’re seeing this “outlier” worldview take over educational institutions, federal policy in the US and Canada, and even corporate marketing; (2) these extreme left outlier views now form a fairly seamless join with mainstream liberal thinking and speech norms. Biden tried to make a disinformation bureau to take advantage of the hysteria around “harmful speech,” a trend which only five years ago was deemed a minor phenomenon on college campuses. Political correctness is extremely prominent and deeply ingrained in lifelong liberals such as myself, and a major force in culture, not just a minor annoyance that can be ignored.

Thanks for your nice reply. Sorry my comment was so long. It’s not appropriate in a forum like this. Also, it was rather critical of a mostly-great post. In fact, this paragraph made it into my lifetime quote collection, and I’ve already quoted you in my public writing:

“Our motivation to stay on the good side of the tribe is deep, deep, deep. Prehistoric. Prehuman even. We really don’t want the other humans to kick us out of the club. Just as our survival instincts draw us powerfully towards foods that are high in fat and sugar, and low in bitter toxins or smelly pathogens, we’re also drawn towards the speech and social behaviors that will keep us in the good books with others. We learn to sniff out which ideas are sources of social nourishment in our world, and which are social poison.”

If you haven’t already, you MUST watch “Chimp Empire” on Netflix. It might be the best thing ever done with motion picture cameras. Having watched it, this quote of yours jumped out at me.

In your response to my comment, it seems that you miss my main point: that nice-guy-ism is slow suicide, and we don’t have time to play patty-cake with insane views derived via magical thinking and fundamentalist belief in mythologies, whether in the Bible or in our propagandistic American history books. A corporate president and a corporate government are suicide, whether polite, slow suicide (Biden) of rude, augmented, rapid suicide (Trump).

It’s not an opinion but an observable fact (which EVERY alien sociologist would report back to its planet) that the war in Ukraine is a proxy war, that the US doesn’t care about Ukrainians any more than we cared about Vietnamese and Iraqis, that 45% of Ukraine is already destroyed, MOST of its children are already traumatized for life, soon most of its men 18-44 will be dead, and soon Ukraine, like Vietnam and Iraq (“Operation Iraqi Freedom” LOL), will be a poisoned wasteland. Another fact is that we could negotiate with Russia today — both sides have good and substantial things to offer. Crimea has been part of Russia since the 1700’s, and was given to Ukraine as a bureaucratic slip-up when Ukraine was still PART of the Soviet Union.

So Mr. Cain, are you for sending Abrams tanks and F-16’s or are you one of the few remaining American “liberals” who haven’t been brainwashed into the prevailing “deep deep deep” chimp empire official narrative, and who are willing to give peace a chance?

Scroll to the Jeffrey Sachs interview in Amy Goodman’s show yesterday. Do you know who she is? https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/democracy-now-audio/id73802554?i=1000614306174

@jeff:

Ah, I think I get what you mean by nice-guy-ism now. I actually don’t advocate that. I think some perspectives are absolutely terrible, make no mistake. But espousing which views I think are good and terrible in this post would distract from its point, which is a meta-level argument about belief itself that should apply regardless of which particular positions the reader holds on today’s issues.

Still, you have to entertain and revisit views that you currently find objectionable if you’re not going to get stuck. I dismissed religion as fundamentalist hot garbage for most of my life, for example, and that was a mistake. There was something to it I wasn’t seeing, even though it has never been harmless.

Jeff

Great insight article. Aptly depicts the role of oxytocin in human relationships and thinking. But we have to find ways to get beyond hormones, as real as they certainly are. “Do you believe what you see, or see what you believe?”. Do you want truth or comfort?

I think our battle ultimately is between the older, more reactive parts of our brains, and the newer, more reflective parts. It’s the human condition really.

Excellent writing David. It feels a little like a new era in your content lately, and I like it. I try to avoid taking a side on anything these days, my life has never been more peaceful. And I know I’ve turned a corner because after spending the last 2.5 years banging my head against a wall, now when certain previously unmentionable things from the last 2.5 years are now quite mentionable, I just don’t care and I love that I don’t care. As Richard Carlson said, don’t sweat the small stuff, and it’s all small stuff!

Today I learned “human rights” are small stuff.

First, if you’re going to go for the compassionate approach, you might want to avoid degrading terms like “transgenderism”.

Second, you’re doing a lot of heavy lifting when you assume moral complexity on hot-button topics. Issues like the abolition of slavery, equal rights for women, segregation and gay rights saw a massive amount of public debate, opinion and a variety of perspectives. Yet the correct answer to all these issues is quite obvious. People feeling strongly about something and having various perspectives does not make it a morally complex issue. It just means that it’s divisive.

Ah, classic debate. You know the subject that will be debated, but you don’t know which “side” you will be debating until it’s on. An entirely different research and thought path than merely defending one viewpoint.

I feel inspired, thanks David. Though I like to think of myself and nuanced and open minded, while reading this article, a few political topics came to mind where I’ve blatantly put the opposing belief into a simple little box.

Aside from actually talking to people about these topics, any thoughts on how to go about doing solo research in such a way that I might get a better understanding of the strengths of these alternative positions?

I don’t have a sophisticated method for doing it. Mostly I follow writers on various places on the spectrum who comment on contemporary topics. Reading them all, I end up getting various perspectives on the same issue. Sometimes I will google “What are the main arguments against X” where X is a thing I suddenly feel pretty certain about. Often it returns threads on quora or reddit, and usually they reference writers or philosophers that you can then look up.

It feels really good to do this. Because you’re getting opposite slants on the same day, so you have to loosen your own allegiance to either of them, and so you don’t feel this usual need to prop up one opinion and cut down opposition to it. You can be a free agent.

The challenge is that the vast majority of us assume our views are objectively correct. Like I KNOW the earth is round, guns are bad, and social nets are important. But there’s no possible chance I’m right about everything. I really do want to know those other sides of the story, that the proverbial ‘evil fox’ has a hungry family of cubs at home. Similar to ‘evil poachers that kill Pandas’ turns out they are poor and starving people in desperation for money.

Some part of me also wants some crazy conspiracy theory to just once, be 100% correct. Like one day scientists are like “hang on everyone, turns out they were right – the earth is flat, or COVID shots actually have Bill Gates’ microchips in them.”

Conspiracy theories are an interesting topic all of their own. I grew up trained to mock anybody espousing a view that even gets _called_ a conspiracy theory, even if it’s just by its critics and not its proponents. It’s an easy way to dismiss an idea without investigation. The term is a red flag to me now, because it’s mostly used as a term to stigmatize ideas without entertaining them. It allows a person to lump together ideas like flat earth with completely plausible claims of corporate malfeasance, for example.

This is a great post, and it was quite bold of you to write it, including taking an explicit stance on issues of speech. Like you, I find it very difficult to sympathize or engage with people who are advocating restrictions on speech or equivocating speech with violence. Though I also hope this blog doesn’t shift too far toward political activism :).

Regarding the content of this article, I find one way to practice exposing yourself to “the other side” is to find issues that are slightly wonkish or mathematical, where the tradeoffs can be articulated more clearly and the abstraction helps you step outside of the emotional component. Examples might be the debt ceiling debate (in the US) or increased federal health care transfers to the provinces (in Canada). Probably most people have an intuition about how these transfers ought to be changed (should there be more? less? more conditions? etc), and engaging with “the other side” can help reveal how other people think about healthcare. Then it will be perhaps a bit easier to wade into a more loaded topic such as to what extent private practioners ought to be allowed to operate.

I also find that it helps a lot to find “reasonable” publications from somewhere on the political spectrum that you don’t like. If you tend to be a conservative maybe this means The Tyee (though they sometimes get onto certain hobby horses that can feel more partisan than productive — right now such a topic is the Albertan election — and it’s maybe best to skip those), where you can read well-reasoned articles in defense of unions, or indigenous rights, or limits on the resource extraction industry. If you tend to be a liberal perhaps try The Hub, which argues for limits on federal powers/spending, for use of police powers in addressing societal drug issues, or in defense of conservative views on speech/wokeness/whatever. In the US there is the Niskanen Center which literally identifies as “moderate”, and publishes articles in defense of moderateism.

As a final thought you can find publications which are obsessed with some non-partisan issue that you mostly agree with. You will find that many of the authors disagree with you on partisan issues, but you know you have some common ground and this can help bridge the gap. Perhaps this is Jonathan Haidt’s “social media is making kids unhappy and fragile” blog, or the New Atlantis “we should be much more careful about the ways that technology interacts with society”.

I don’t have a good way to *find* these sorts of publications. But when I get linked to them I try to glom onto them.

Thanks Andrew. I appreciate the suggestions and have subscribed to the Tyee and the Hub. I don’t know where I am on the political spectrum right now — grew up liberal but the left is now less liberal than the right so I’m not sure what to make of it all. Letting go of my old “training” has allowed me to consider voices from most of the spectrum. It is a very weird experience but very liberating, because I don’t need to force myself to reconcile my inherited beliefs with uninherited ideas that seem to make sense.

I don’t intend to let this blog become too overtly political, in the sense of partisan activism, but I have always been interested in beliefs as such and I want to discuss them on a more meta level — where do we get our beliefs, how do we inquire into the truth, etc.

As for finding new publications, I’ve been making good use of Substack, the newsletter platform. The style varies from conventional journalism to personal rants, and they tend to link to each other often, including the people they disagree with.

I have a similar political story to you — tending toward the word “liberal” but finding its meaning has shifted to mean something quite illiberal. Today most of my strongly-held political beliefs are related to cryptography, surveillance, privacy and censorship, which are all technical and obscure enough that there aren’t political tribes around it. It is indeed freeing somehow not to have any team to feel obligated to support.

I really like the idea of exploring “where do we get our beliefs, how do we inquire into the truth, etc.” on this blog. It seems that some incredibly powerful industries have formed around undermining these processes in our minds, and the result is hyperpartisanship … and also anxiety, confusion, and difficulty empathizing, which are all longstanding themes of this blog.

Hi David,

Long time lurker here. Don’t think I’ve ever made a comment before.

I read your recent “how to think about politics…” It gave me a slant that I hadn’t thought of before, that I was hoping you’d elaborate on (but didn’t so far). That is that when engaging in reading or conversation with others whose ideas are so divergent from my own, what should be uppermost in my mind is not the facts of the case, but rather the social/historical conditions the others have been exposed to and relate to through their beliefs. “Facts” second. (In fact, I’ve read a number of things in websites that are otherwise relatively sophisticated philosophically, where the writer refers to “evidence” as a foundation, without deference to the understanding that what counts as evidence is relative to one’s perspective, and what is evidence from one is not from another. Think of the billboards I have seen around me in Philadelphia that state “there IS evidence for God.”)

What groups one identifies with, how one thinks of one’s own identity, who one interacts with regularly and in what context (on-line is one thing, talking at home or at work another….) are all things that are relevant. How is a person able to grasp enough of that to make sense of what is coming at them ? How far down the rabbit hole do you have to go ?

An additional terminological comment (pls, no need to make this public !): from a psychologists view, you are using the label “Pavlovian” incorrectly. Pavlovian association has nothing to do with reward/punishment or the action of the subject. The term you want is probably “Skinnerian” (or to be more esoteric, “Thorndikian”). Of course neither of these terms has the cache of “Pavlovian,” so maybe the meaning of that word is stretched out now. Just thought I’d mention this mainly because it bugged me, not because it affects what you’ve written. In the same nit-picking vein, I am wondering if you meant to use the term “equate” rather than “equivocate” in your last paragraph. I think they both work, but since “equivocate” refers to ambiguity and doubt (good things, I think, in the context of your essay) and “equate” to sameness and the ignoring of distinctions, I think that is a stronger statement.

Anyway, keep up the good work. I’ve saved this essay with others in my to “re-read occasionally” list.

Yours,

Larry More

Agreed — the facts are pretty far down the list of what influences our positions on things. They are relevant but not nearly as relevant as the identity stuff. “What kind of person would say ‘X is true?’ seems more salient than ‘is X true?’ to a creature highly preoccupied with its social standing with others. I think it’s just that: what’s true is less important to our instincts than whether we’re safe.

By Pavlovian I just meant “a conditioned response.” It seems to me that operant conditioning is a specific form of that, but yeah I was conflating the two.

re: equate vs equivocate. You’re right. I usually hear the word equivocate used in the phrase “false equivocation” which after looking it up, seems redundant. I probably should have used the word “equate” in that sentence. It was a reference to equivocation though.

Great post! I actually studied a master’s degree in social and political science and a master’s degree in public administration because I wanted to understand. Being a sociologist is hard because it’s as if a doctor had to witness all sorts of non doctors giving medical advice to strangers with utmost certainty. However, after my studies I no longer get angry watching the news. I feel no anxiety about the future. Yeah, there are a lot of problems, but no, there is no single culprit and there are no easy and fast solutions. So now I live in this sort of political nirvana where politicians and parties don’t matter and the only level of conversation that’s interesting and productive to me is about systems and system incentives. So I might add to your post that political sophistication is really worth it, you get a lot of peace from it.

Comments on this entry are closed.