Time always feels like it’s speeding up, but you might feel like time has been going exceptionally quickly these past few years. The first few days of a new month quickly become the 11th, then the next day it’s the 23rd, and then your credit card is due and it’s a new month again.

It might also be hard to remember, when people ask, what you did with those weeks and months. “Oh, I’ve just been, uh, working and stuff, I guess” you might say, when you bump into an acquaintance at the grocery store.

For some of us, the 2020s have also come with a certain lingering mental fog, or poor memory, which is another reason it can be hard to generate an interesting report about what you’ve been up to.

Naturally I have a theory about this, maybe even a cure. The hypothesis I’m about to share is not entirely crackpot — there is some scientific evidence behind this, but I’m mostly going off of my own intuitions here. Tell me what you think.

Basically, I believe the time acceleration and mental fog are mostly symptoms of the same problem: a lack of a certain life ingredient that suddenly became rare, virtually overnight, about four years ago. This ingredient is much more available now than it was then, so the problem can be remedied, but you do have to go out and get it.

As I write this, we just passed the four-year mark since the coronavirus pandemic blew everything up, beginning on that surreal week in March 2020 when they canceled the NBA season and told us to immediately stop touching our faces. In the following days there were mass closures, layoffs, and drastic new rules for everything. Each day of that month there was a new development, and each day our lives changed. As many have said, it felt like the longest month in history.

Then the “new normal” set in, and the pages started flying off the calendar. The next four years went by in what felt (to me at least) like about eighteen months, and here we are.

People have always remarked that time seems to speed up as you age, which I’ve written about before. The sense of time accelerating is usually explained away with the idea of proportionality — a year to a one-year old is a lifetime, while to a centenarian it’s 1% of a lifetime.

I don’t buy that explanation. Time’s apparent “speed” changes with conditions, as we’ve all experienced. A week spent in a foreign city feels much longer than a routine week spent at home. In an unfamiliar place everything is novel, so it has to be engaged with more care and attention. In order just to manage everyday tasks, such as buying lunch or crossing the street, your mind has to do a lot more than it does at home. More details must be noticed, evaluated, and marked by memory for later. Less of what you experience can be navigated by habit or reflex, so you can’t spend much of your day preoccupied with your familiar and repetitive thoughts. Such a week simply can’t pass by unnoticed and unremembered.

In other words, periods of time that contain more novelty and variety pass slower and leave bigger, brighter memories. That’s why the more “foreign” the destination city is, the longer a one-week visit feels. An American tourist could walk down Dundas Street in Toronto while entirely preoccupied with their usual thoughts about home and work, remembering little of the experience; walking down Bangkok’s Khao-San Road while barely noticing it would be almost impossible.

The reason time seems to speed up over the years is that novelty naturally declines as we age. Life’s elements become increasingly familiar and routinized. You take fewer risks, become less adventurous, move house less often, change jobs less, meet fewer people, stay home more, and so on.

You can probably see where I’m going with this. When the pandemic emergency was declared, we were at first catapulted into the unfamiliar. Over only a few weeks, we had to adopt all new ways of living, working, socializing, sanitizing, entertaining ourselves, and thinking about the world. That few weeks felt very long and was very memorable. This is what happens when novelty spikes.

After that, novelty plummeted. Lockdown quickly made life very samey. There was so much less we could do, physically and legally. We interacted with fewer people, moved around less, and canceled new endeavors. We stayed much closer to home, in every sense.

For some of us, this sameyness came along with a certain mental fog: cognitive dullness and poor memory. People have suggested many explanations for it: too much screen time, additional stress, long-term effects of the virus itself, culture-war-induced despair, lack of exercise, and others.

It might be partly those things, but I suspect much of it is just what happens when variety and novelty disappear from life. A mind that is essentially being prevented from encountering new people, spaces, and sensory experiences isn’t going to remain at its sharpest.

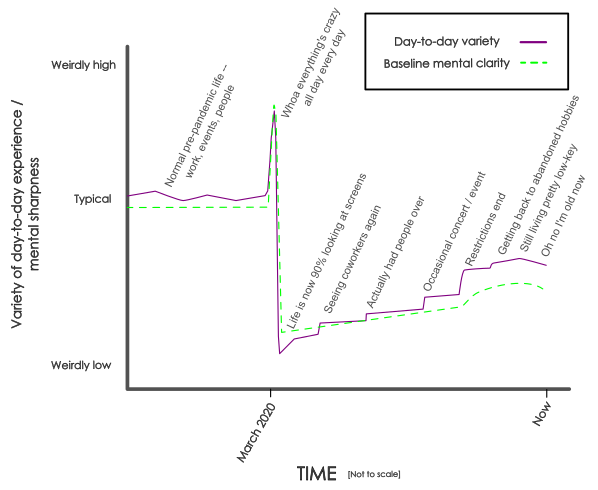

Under my pet theory, as the variety and novelty of day-to-day experience go down, mental sharpness declines with them, while time seems to speed up.

If you graphed the last five years of this phenomenon, it might look like this:

My layperson’s grasp of the science behind this relationship is that novel experiences induce dopamine release into the hippocampus, which triggers the formation of memories. That makes evolutionary sense: if you discover something useful, like the location of a food source, you want to remember it.

There are two kinds of memories, however: semantic memories and episodic memories. Semantic memories are about factual information. Reference material. What color grass is, what temperature paper ignites at, what the flag of Italy looks like. This is information anyone could know, and exchange with others.

Episodic memories are the autobiographical ones, and they’re stored in a different place in the brain. These memories concern what happened in your life, as it relates to you: that you rode a gondola in Venice, that you gave birth to a baby girl, that you studied ancient languages, that you once saw James Gandolfini at a restaurant.

According to the study linked above, episodic memories form as a result of distinctly novel experiences — ones that “bear minimal resemblance to past experiences.” When the mind encounters a whole new category of experience like this — as a result of trying rock climbing, meeting new people, or walking unfamiliar streets — it encodes a lot of new information, and changes something about who you feel like you are. It adds to your story. You now feel like a person who has climbed granite slabs, knows Wendy G, and ate street food from a paper cone in Bangkok.

If you’re living a more routine and constrained life than you did five years ago, perhaps absorbing a lot of content and information but having fewer distinctly unfamiliar experiences, you’ve probably been forming fewer episodic memories. Consequently, life during that time might seem thinner and less significant in retrospect. It will seem to have gone by faster, and will be harder to recall. It might seem like you just got older and little else changed.

Most of us probably still haven’t made it back to pre-pandemic levels of novel experience. For many people, life got permanently smaller and less varied, with a smaller social circle, fewer events attended, less travel, less going out, less genuinely new material encountered by the mind. You may have become more cautious, more routinized, more of a homebody, and stayed that way. I know people that haven’t even gone to a restaurant in four years.

The remedy then, if you feel like time’s going too fast and the mind is foggy, is to try to get the variety level back to where it was, or as close to it as you can. That could mean reconnecting with some people, meeting new people, attending events, traveling, moving stalled projects forward, or taking on entirely new ones. Anything but the same things you’ve been doing.

If my hunch is right, you just need to get life back to a state where new experiences happen regularly again, and then the weeks and months will be unable to slip by unnoticed.

***

Images by Jurica Koletić, Florian Wehde, Chris Montgomery, Dino Reichmuth, and David Cain

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

{ 57 Comments }

I’ve been a subscriber for at least a decade now, though I haven’t always checked my RSS. But I’m unsubscribing now. Honestly what I read felt like intellectual masturbation.

I’m listening to Ajahn Sumedho now, and even as i listen to wonderful teachings about present moment experience, I know that having an open heart and mind sometimes means not being neutral. There was so much abuse in the COVID times, blaming those who question, and it cut through mindfulness societies. There were those who ignored the reality of decaying society and those who saw and were simply present with it, connecting with each other and wanting to get past double speak. Truly being with the suffering of others. That’s what mindfulness should be about – being in another’s world, being present, especially in times of intense suffering. But there’s always been a love and light side of mindfulness in the west, creating bubbles instead of stable foundations. Vietnamese Buddhists stoof up for each other, with compassion, with firmness.

i remember being in India with a Zen Master who said that there isn’t real Buddhism in the west yet, because there’s no Sangha in depth.

Bye then!

Dear Matthew, I too have followed David’s writings for over a decade and feel your un-Zen-like response is totally out of place. I’m guessing that you’re upset about many aspects of the pan/scam-demic — like very many of us are — but I hardly think David is to be blamed!

What a horrible response to such an interesting subject that a lot of us experience and wonder about. You present as being either an extremely arrogant person, or very unhappy with your life–something amiss.

Before you go, can you at least tell me which part of this post you’re reacting to? It isn’t clear from this comment.

Btw I agree with you that there has been a lot of abuse, and that many mindfulness communties in particular self-destructed. I would like to hear your thoughts about that.

If your concern is that I am too credulous towards the official “approved” response towards covid, I’m not. I have a lot of beefs with what went down but I didn’t want to make this a culture war post.

Why does it matter that time seems to pass quicker? It’s illogical: you get the same amount of time however it’s experienced. The counterpoint at least in my life to what you are saying is that maybe the slowness of time also relates to perceived threats and unpleasantness: I used to spend 50% of my waking life in an environment where I was frankly miserable, surrounded by people whose company I did not enjoy and would not have chosen to if my livelihood did not depend on it. Regularly I felt the insecurity and boredom of being in an office and that made time pass slower. Now I only do work that I find valuable and I spend about eight times as much time with my children whose company (while not always pleasant!) I would seek out any day of the week. There’s less variation for sure but my flight or fight hormones are activated far less too. The pandemic re taught us (at least me) the most valuable lesson of Candide: Il faut cultiver notre jardin.

In my experience, this has been the greatest aftershock of the pandemic. People were hit with the reality check that life is short.

This huge shift manifests in small ways; for example, we bid by seniority at my job, and people routinely now pass up 40-hour shifts for ones with more time off.

Have you never been surprised that something you thought happened a year ago actually was two years ago? Or that you look back on the year and didn’t get done what you thought, and can’t believe it’s already fall / winter / the new year? If time going too fast isn’t something you relate to, that’s probably a good thing :)

I totally get the speeding up thing – it started in my twenties and has been accelerating ever since. I just dispute that the pandemic was a catalyst for this in a solely bad way (and also that it’s necessarily a bad thing). I also agree that it’s probably related to “number of experiences” just not solely interesting or good ones ones – I think it’s also related to the number of unpleasant or scary experiences too.

Another thought is that I suspect that everyone experiences this decline into relative boredom. It’s called settling down – my body just couldn’t put up with the insane things I did to it in the past any more. What the pandemic did was to put an unnatural pause on things so it really allowed us to focus on this rate of change.

By the way, I love your articles. If I seem to be disagreeing (or disagreeable) it’s just because you provoke such interesting thoughts.

Seems eminently plausible to me. Plus the graph made me snort coffee out of my nose, which is a good thing. Thank you David for your continuing thoughtfulness and wordsmithery.

Making people laugh is always my primary goal

You are so right. Also lockdown for many people instigated a kind of trauma. I was living alone at the time and had no bubble. Friends seemed to retreat into their couple bubbles, seemingly with little awareness of the extra pain carried when alone. I wasn’t coping well and then it became worse. My 90 year old father became ill – instigated not by Covid but by the restrictions. in march 2020 I moved in with him and nursed him through his illness till he died in July. My brother died one month later. Lockdown for me represents a hole in me and my life that continues today. In 2022 I decided to begin holidaying alone and now I think I live for that week, which feeds for the rest of the year, through the job and the day to day banalities and emptiness. I yearn to do more, walk more, but I have developed a foot problem caused largely by covid weight gain. I’m trying to sort this as best I can, but age and money get in the way. To everyone out there – get off your phones and experience the world in all its wonderful detail – because detail and observation expand time.

Totally agreed that detail and observation expand time. I really think the apparent speed of time ultimately comes down to how much of the time we’re actively attending to our surroundings, and how much time we’re attending to thought, because thought is repetitive and distinctly un-novel. Mindfulness expands time, and I think this is because you’re attending to everything as though for the first time.

Good piece, thanks David.

I think tree’s a lot of truth to what you’ve said, and I think electronic devices also set this off before the pandemic. I do my share of traveling, and in most cases, if I’m on a bus/train I have headphones on and I’m listening to my favorite music, reading a good book, or binge watching a tv show. I’m not looking out the window or talking to the people around me.

I think “mindfulness “ plays a factor. If you’re paying attention to the sensations of the temperature of the water and the scent of your shampoo in the shower, focusing on nature or events while you’re out walking, or focused on every bite you take while you’re eating then you’re more likely to remember it and the time passes slower while it’s happening.

If you are on “autopilot “ then things just start to run together. If you’re out of work, and home every day in a routine, you can easily start to lose track of what day it is. That might be why most of us have the date on our screen locks. And if your phone resets automatically for daylight savings, you don’t need to pay close attention to making sure that you do it.

The pandemic increased being home in a routine, but I was working twelve hour days and if you’re on autopilot at work, taking a quick shower and eating cereal for dinner and then falling asleep it all goes by quickly.

Reading a really good book should slow things down because you’re paying attention and stimulating your mind, but how often have you picked up a really good page turner, become engrossed and felt like the past four hours was five minutes?

Electronic devices are definitely a factor, and the pandemic certainly accelerated their use. I would love to see data (which is probably impossible to collect) on how rates of content consumption went up. I suspect across the board became more “autopilot” on a population level.

I’m in the last year of my PhD and the number of days I have left to actually write my thesis is rapidly approaching double-digit territory. However, because I am a master procrastinator, in the last 4 months I have learned to ride a motorcycle, moved house and begun taking piano lessons. So I guess your theory would explain why I feel like time is passing incredibly slowly – but meanwhile, the slower it goes the more time I get to spend feeling guilty about never actually writing anything…

Hey, productive procrastination is a thing! You’re doing it right :)

I always heard that times speeds up as you age as well, but I work with a lot of very young people and they all feel the time acceleration from year to year as well. It’s definitely not tied to aging per se.

I’m trying to recall if I noticed time acceleration when I was a child or a teen. I don’t think I really did until my 30s or so? Incidentally this is when life became a little more stable and routinized.

Great article and mostly agree! I think one thing you may have left out is some of us realized when the world pressed pause, that it was our chance to reevaluate how we spend our time and what will lead us to fulfillment and happiness. For me, I was eager to move on from socializing being the only real thing I pursue outside of work, and COVID shutdown was a great catalyst to move on that.

I will say I think I need more novelty and I fully agree that contributes to the feeling of the speed of time, but I don’t want to go back to the same ‘novel’ things I was doing before (which had become pretty routine) and am still working on putting everything back together in a new way.

Also, if you travel enough, that eventually becomes routine as well, or requires you to go to even farther away places.

That is a good point. I remember a phase in which a lot of the discourse around the jarring effect of the pandemic was that it was forcing us to evaluate life and how we want to live.

The thing about novelty is that returning to the same things isn’t novel. I think it really comes down to how attention ends up getting used — how much of life is spent in a state of inquiry or engagement with something you don’t quite understand, or haven’t yet tagged and conceptualized and made into thought, if that makes sense.

Hey David,

always love your thoughts and regular appearances in my mail (i dont read a lot of the newsletters that i have subscribed to, but i have never missed a text of yours).

I relate to your findings and feel the need to go back to reading Manns “Magic Mountain”, since he has explored the concept of time in a unsurpassed manner. So -> recommended reading in case you havent already :)

warm wishes from switzerland,

Dani

Ah, thank you, I will check it out

Interesting brain science behind the formation of episodic memories. I agree that many of us still haven’t gotten back to pre-pandemic levels of novel experience. My life is vastly different from the life I had before March 2020. Even after we were told it was safe to return to normal life, I found that the forced isolation had provided an opportunity to reassess my life. And some positive things came from that. I eliminated things that had just become habit but that hadn’t been providing me much joy, and found more satisfaction in tending to my home and garden. I’m pleased with that change.

But I think there’s another factor that’s keeping me from returning to pre-pandemic levels of activity, and it’s related to the political turmoil in my country (US) at that time. The pain of finding out that some friends and family members refused vaccines and spouted conspiracy theories was intense for me. And then there were the unbelievable events of January 2021, piled on us before we’d healed from the trauma of the pandemic. The turmoil surrounding politics impacted me deeply. As much as I wish it wasn’t so, these days I go out in public wondering who around me might have been one of those who caused so much turmoil in our public life. My feelings about my society have been forever altered, and I guess I’m still trying to protect myself from having to experience those feelings on a daily basis. So a reduced participation in “normal” social activities is my way of holding on to whatever peace I can find closer to home. And if that makes time seem to go faster, maybe that will have to be okay with me.

David, as always, thanks for giving us things to think about.

The culture war stuff certainly ramped up. Certainly we’ve become more polarized, and I’m sure a large part of that is a result of more content consumption that was inevitable over the course of the pandemic.

One upside of observing all of the partisan suspicion and arguing is that I’ve become a lot more aware of how wildly different people’s worldviews are. We are living with completely different conceptions of what is happening in the world. That seems so clear to me now that I actually have an easier time getting along with people I disagree with, because literally everyone sees the world differently than everyone else.

Yes, I agree that it’s good to recognize that there are so many different worldviews out there. Excellent point.

“My feelings about my society have been forever altered, and I guess I’m still trying to protect myself from having to experience those feelings on a daily basis.”

I have had this experience as well, I was not prepared for the level of vitriol spewed. At first I believed that we would rise to the occasion and we did not. I lost 50 year friendships over it.

I appreciate the thought and structure you put into this piece. I appreciate the Truth In Packaging label you put on this, which came from your life experience: “Naturally I have a theory about this, maybe even a cure. The hypothesis I’m about to share is not entirely crackpot — there is some scientific evidence behind this, but I’m mostly going off of my own intuitions here. Tell me what you think.”

Variety and novelty became off-limits during the pandemic isolation and quarantines. There’s another factor here and some of us saw family members die. The longtime playmate and spouse who was my constant source of variety and novelty died. So there’s the source of variety and novelty, as well as other factors you pointed out to work into the New Now. There is no new normal. There is only a new now.

There are tons of variables here, absolutely. It has all been such an ordeal for everybody. My hope is that we can find some relatable threads out of the extremely complex last few years.

David, first of all I love your blog and I am so happy you’re still regularly posting (yours is one of two blogs I actually still read). I partially agree with you here and it might be the case for others but I feel it’s not the case for me. I really struggle with time moving at an increasing speed and kind of feel like I’m on a roller coaster downhill screaming “make it stooop!”

At the beginning of the pandemic I experienced a lot of life changes – new boyfriend, hence a whole new friend group to socialise with, lots of traveling together, moving, then moving again to Cambodia, having a new job there, having another job there, moving back to my parents, etc… anyway so much happened and it all happened so incredibly fast. I also feel nostalgic all the time. When I was living in Cambodia I missed my friends at home and now I’m back in Europe I miss my life in Cambodia.

Do you have any advice on how to stop feeling so overwhelmed by how fast time is moving for someone like me?

Aside from the ideas in this post, the only reliable way I know is to take on a somewhat serious mindfulness practice. It really slows down time and brings significance to the ordinary. The stronger my practice is, the slower time gets and the more I feel I’m able to use it well. When my practice wanes, it the opposite happens.

You’re on to something here David. I retired from a busy and fulfilling, 30-year career during the pandemic. My retirement was a function of preparation intersecting with opportunity, so I jumped. All this to explain that I’ve noticed during retirement that when I’m intentional about programming my days in ways that ensure interesting tasks, activities and interactions, that I feel productive and fulfilled and the ROI of my time seems high. To the contrary, if I become lax about planning my day just because I can, the time seems to quickly evaporate and I’m disappointed in myself for not having squeezed more enjoyment value from this limited resource.

It reminds me of a time while in my youth when my Dad asked me how my day was, to which I responded, “it was nothing to write home about…”. To which he responded, “well shame on you then, you should do more with your time”. :)

Hola! Mi año 2018 desapareció ,no sé como ! ,cuando me quise dar cuenta era 2019. Que había pasado? Empecé a leer por Internet sobre el paso del tiempo, sobre la percepción del transcurso del tiempo., y durante esta búsqueda llegué a tu blog, precisamente por el tema de hoy!! Yo no tengo niebla mental, ni mi tiempo transcurre más rápido..Me encanta escuchar teorías, posibilidades,..puede que sea así. El conocimiento no comprobado sigue siendo conocimiento, aunque no se distinga de lo que no lo es. En mi caso, después de la pandemia he vivido en 4 poblaciones diferentes, y tenido 3 trabajos diferentes desarrollando mi especialidad. No tengo vacuna covid ( porque no está suficientemente desarrollada), y practico directamente atención plena, sin meditación, no sé meditar. David, espero que te sirva.

I don’t mean to diminish anyone’s pandemic experience, but it really didn’t affect me much. I was already working from home running my own business. I switched to working out at home and stopped going to restaurants, but my day-to-day didn’t change much, I didn’t feel all of the isolation and mental issues that I hear so many people talk about. I almost feel bad for admitting it didn’t affect my mental sanity.

I feel the time going fast thing though. I’m going to try your suggestions, thanks.

Isn’t the search for novelty and new experiences an integral part of our current version of capitalism? Hence part of our insecurity and alienation from life and the non-human world. Travel all over the world etc.I am reminded of the great Dogen’s words: “To carry oneself forward to experience many things is delusion. But for many things to come forth and experience themselves is enlightenment.”

Your article really made me pause and reflect. It’s so true how time seems to slip through our fingers, especially these past few years. I’ve been trying to combat this by introducing more novelty into my daily routine, like trying a new hobby or even taking a different route to work. It’s amazing how these small changes can make my days feel more memorable and substantial. Thanks for the nudge to be more intentional with my time!

Synopsis of the movie A Slip

To carry oneself forward to experience many things is delusion. But for many things to come forth and experience themselves is enlightenment.”

It isn’t just the minimization of life caused by the pandemic that generates this problem, but the fact that as you get older, the amount of novel things you can do necessarily decreases. You can only visit a foreign country for the first time one time. If you go to Thailand in 2022, then Japan in 2023, then Singapore in 2024, these cities no longer start feeling so foreign. You can only ride your first roller coaster once. You can only have your first romantic relationship once. Each subsequent one has novel aspects, and some familiar aspects. There are a lot of new things you can do as you get older, but not infinite. Even the novel things that you do have aspects in common with other things that reduce their novelty. I agree that we can try to to maximize the life experiences that were taken away by COVID, but there will be diminishing returns.

True novelty definitely cannot be recreated, or it won’t be novelty. However, you don’t need an endless supply of truly novel experiences to have this effect. No experience is truly repeated anyway — you can read a book for a second time and you will not have the same experience of it. Just doing something you haven’t done in a while still activates the inquisitive part of the mind, you still have new feelings and insights while doing it, you still form episodic memories. This will always be better than an unvaried routine in which you don’t change the scenery often.

Great post. I liked the concept of novelty removing the fogness of the mind. Guess if we are static at home, we can enhance our semantic memory. But I prefer working on episodic one. Regarding COVID, since I live in Japan, this was my gold time when I travelled the most and enjoyed empty trains and cheap hotels. Every week was like a month!

I think your observation hits the nail on the head David!

Last month, I was travelling overseas in Japan for 20 days and it distinctly felt like an eternity because each day was so different and novel, but since returning to my routine, an entire month had passed in the blink of an eye. Crazy.

I agree! As someone with diagnosed ADHD, I crave novelty (while needing stability), which meant that I probably took more risks soon after the vaccine than most, but I felt like I had to. Maybe it was an impulse control thing. I just knew I couldn’t survive the monotony much longer. In terms of memory retention, I’ve had similar experiences. I studied abroad in college and, in a nostalgic way, could smell Tokyo and Rome for years.

The greatest distress I felt during early Covid times was hearing on CBC: “I’m 83 – I’ve lived a good life – all I want to do now is to hug my family and my new granddaughter, but the won’t let us out, and they won’t let them in!” What was the passage of time like for them? Very long days I will guess.

I empathize with all souls seriously affected by the Covid phase. But my experience of ‘the velocity of time’ was quite different from that of most.

I’m older than most. I was 77 when Covid happened, ‘retired’, gardening and renovating our house, room by room. And although I saw what has happening around me, there was, apart from ‘passports’ at restaurants and wearing masks where it was illegal or grossly inconsiderate not to, I felt no appreciable change in my lifestyle; my sense of time passing didn’t change noticeably. This could be in part because my wife and I don’t have news subscriptions, radio or television, so we weren’t seeing daily into the lives of those suffering the most.

Plus, our children all lived far away, so laptop and cellphone contact was all we had; they would comment more than complain about the Covid restrictions, even though they were living the home-kids-work lifestyles. One was a health care worker and the other two had online businesses from before Covid. So luck played a part but perhaps inherited/modeled attitudes did as well. Attitudes matter, and are both inherited and learned.

I was born two years before the end of WWII and was raised by parents who had lived through two World Wars with a Great Depression in between. Their parents were unemployed throughout the Depression years. The people my parents became had lots of stories to tell, many of which ended with “… but there was no alternative – we had to keep going.”

The point to all this is that I have come to believe that hardship is just part of life, and though I can feel shattered by big personal events, usually I get back to being able to ‘just roll with it’.

So, whatever the reason, I felt like a somewhat bemused observer during the Covid period. I took peoples fears seriously and compassionately, but didn’t feel fear myself. Era conditioning again? I simply wasn’t afraid – I even got close to anyone I could and tried to get Covid in order to gain natural immunity – in line with something I was taught growing up “The immune system needs bugs to practise on” and “You have to eat a peck of dirt”. (Baby would pick up a fuzz-covered soother off the rug and stick it in back in her mouth, then grimace and work her little tongue; “she’ll figure it out” was the adult comment.)

Finally, chicken pox, measles and mumps were rites of childhood – most people got them and some suffered more than others. Vaccinations began when I was in 3rd grade I think.

I may be naive, but Covid was just another flu so far as I were concerned, thus I didn’t notice a change in the elasticity of time.

Thanks for this Tom. I appreciate hearing different angles on the covid era, particularly because the reporting has always been from a fairly narrow range of perspectives.

The point of David’s piece seems to be similar to the concept of episodic memory discussed in a recent podcast of Re:Thinking between the host Adam Grant and pyschologist/neuroscientist Charan Ranganath towards the end of the discussion.

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/rethinking/id1554567118?i=1000650379699

I had a knee-jerk reaction when I read this article’s thesis: “What? That’s nonsense, David! I feel like the four years since COVID have absolutely crawled by!” I’m so glad I kept reading to the end, because my personal journey in this time period backs up your intuition 100%, despite coming to the opposite conclusion for myself.

I was fired from my job in the fall of 2019, and my partner and I decided to pull the trigger on a long-term dream and move into an RV to save money and allow me the space to get over the “trauma,” if you will, of a working a job I hated for years. By happenstance, everything fell into place just before COVID hit.

The following three years saw huge changes, good and bad, to our social circle, finances, aspirations, dreams, work, and play, probably some of the same changes everyone reading this experienced. Then, my partner followed me by quitting their toxic healthcare job, and we decided to travel the western US full-time.

You wrote: “Most of us probably still haven’t made it back to pre-pandemic levels of novel experience.” You are spot on, and we are definitely in the minority. We started traveling almost a year ago exactly, and life has been a constant stream of surprises, finding new friends, locales, and work nearly every month. This past year has felt like THE slowest-moving year of our lives.

Consider our story more proof that you’ve correctly identified this link between novelty and the slow passage of time.

Thanks for this example from the other side. Yeah I don’t think there’s anything about covid specifically that slowed time down, only that it probably came with a long period of sameyness for most people.

Btw, congrats on your big move to a better lifestyle. It sounds like you’re really living life.

It certainly does feel this way, things have sped up so much. I think high inflation also contributed to some degree on new experiences once everything opened up again. Me and my wife rarely go out of town for excursions due to costs of hotels and concerts or other events going through the roof. Also try to less new restaurants. I also do meditation and not getting to do my usually retreat or two over the pandemic time impacted my reflections I often get on them. So many things canceled got us out of the practice of doing things too.

Good point. Extracurriculars have become more expensive and inconvenient so many people never went back to them.

Good job, David! You hit the nail on the head. I totally agree with you, that the same, same, same every day dulls our brains, and our experience and memories. you have made me realized I’ve not gotten back to pre-pandemic activity. No time to start like the present, thank you!

I think the novel experience hypothesis is a bigger/likelier factor than the percentage-lived hypothesis.

I do wonder, though, about the relative value of episodic vs semantic memories. I’ve missed out on innumerable episodic memories over these last years, the result being, like it was for many people, that I blinked and then realized my youth was over. But if someone offered to exchange the semantic memories and implicit memories I’ve acquired over the last few years for the episodic memories I didn’t, I’m not sure I’d take up the offer.

Doesn’t real happiness come less from the past than the future? And isn’t the best way to gain future happiness usually to put your nose to the grindstone for a bit, even if it isn’t exciting, and won’t leave much of a trace in your episodic memory?

Perhaps episodic and semantic memory are in conflict less often than I think, and I’m getting worried over a false dilemma. Still, they conflict at least sometimes, don’t they? What do I do in those cases?

I don’t have an answer to what causes real happiness. I would guess it’s very complicated and contingent on the specifics of someone’s life. Having something to look forward to is good, but I don’t think happiness is particularly dependent on remembering or anticipating. I think it has more to do with how you engage with the present. As to the question of what makes time feel slower and more significant, I think episodic memory is pretty crucial there.

Great article. I believe that smart phones, and high speed Internet connectivity to them, has been a major factor in “life is speeding up”. Because, you can now consume and be constantly distracted by meaningless and purposeless multimedia anywhere and anytime. Unfortunately, consumption of pointless content is highly addictive. We are all very much at risk of becoming trapped in the cycle of aimless consumption. We must recognize (and it needs to become mainstream) that we must be highly vigilant to ensure that we consume in meaningful and purposeful ways. Because time slows down only when what we do, what we apprehend, what we interact with, is purposeful and meaningful for us. The vast majority of people that I know consume content from their phones in aimless, purposeless, borderline obsessive compulsive ways. And this speeds up time for them. Which is basically fully in line with your thesis.

It all pretty the opposite if you’re not in the US :)

Since 2022 I’ve changed 3 countries and I’m planning to emigrate to the fourth one.

I’ve had so much novelty and so many things to adapt to. However, time had never run so fast for me as in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine.

So I would guess the perception of time is more connected to your level of cortisol, rather than dopamine.