I live in a land of temperature extremes. In a typical year my city will see both 35 degrees Celsius and minus 35 (that’s 95 and -31 to Americans.) We have the greatest range of temperatures of any major city in the world. Average temperature is slightly lower than Moscow. Humidity and wind chill stretch these extremes further.

Our dramatic climate constitutes a large part of our modest civic pride. It’s particularly relevant to me though, because my day job has me working with my hands, outside, all times of year.

Construction crews know how to build things — roads, pipes, hydrants, and buildings — but they couldn’t possibly build them in the right place without a professional surveyor staking them out. That’s what I do. I read engineering drawings and mark exactly (to the inch) where all the new stuff belongs in the real world. Thousands of years ago, this was done using wooden stakes pounded into the ground at carefully measured-in points, and they have not yet found a better way.

Most construction happens in the summer. I find the points while a student assistant does most of the hammering. In winter, the construction season is on an outbreath and the industry slows way down. The students are gone, so two or three surveyors team up to create overqualified super-crews of stake-holders and hammerers. Many of my workdays, another surveyor does the technical stuff and so I become essentially a manual laborer.

Minus 35 is something everyone should experience at least once. The air shimmers with cold. When you inhale, the inside of your nostrils freeze. Your breath comes out in clouds. If there’s a breeze and some of your skin is exposed, say between your glove and the cuff of your coat, it feels like it’s being cut with a knife. But you wear layers, you keep moving, and you make sure to find a job for the extremities that tend to go numb first.

Worst of all for the surveyor, the ground is about as soft as a brick. Wooden stakes shatter when you try to hammer them in. So we must always first pound in an iron bar to make a hole.

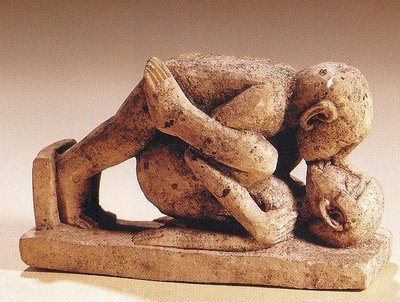

Even with a pointed iron bar it’s almost impossible to make a hole if you’ve never done it before. If you don’t hit it dead-centre, often the bar bounces right out. It takes several great, two-handed swings with a ten-pound sledgehammer to make any progress, which means someone else has to crouch down and hold the bar for the hammer guy.

It becomes a cogent exercise in trust. A miss could be disastrous for the wrist-bones of the holder, but the hammer needs to be swung hard, and we have to do this thousands of times. Being the hammerer is actually scarier than being the holder — I would rather get hit with a sledgehammer than hit someone. After working a few weeks with a particular partner, a person gets less nervous and it feels a whole lot safer. The upside to swinging the sledge is that you stay warm. Read More

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I highly recommend a consistent, daily meditation practice! For years I was interested in meditation, but never did much more than read a lot about it, and think a lot about it... but that doesn't hold a candle to actually sitting and meditating every day. I find it helpful to keep...