Not voting is an interesting experiment.

Having voted in every election since I turned eighteen, two years ago I opted out of two in a row — a civic election and a federal one — to see how it felt to know that what I did on election day didn’t matter.

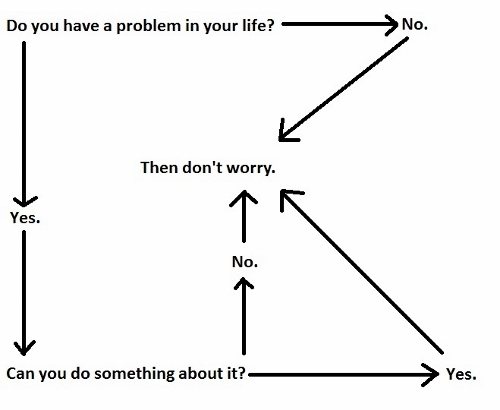

A few months earlier, it had been pointed out to me by a well-spoken smartypants that my voting had never influenced public policy in any way. Removing my vote from the totals would have resulted in the same results — the same government, the same policies — in every election I’d ever voted in.

I kind of knew that, but I didn’t quite grasp what it meant. It meant that if I believe having some influence on society is important, I can’t possibly rely on my vote to do that. But voting still somehow conferred a feeling of involvement, of participation in the shaping of society. So I did it anyway, even though the math shows that if I had chosen to clean behind my stove each election day instead of voting, society would have progressed the exact same way, while the state of my kitchen would have improved considerably.

The following election I stayed home, to be sure I knew how it felt to choose to be only a spectator. I had a creeping feeling that I always had been. I didn’t clean my kitchen.

It feels bad, if you’ve never tried it. It sent me into a bit of a cynical spell on the whole matter of electoral politics, and I wrote about it here: If the election really mattered to you, you’d do more than vote. I think my logic is still solid, but I do regret the antagonistic tone of it. The comment section contains some pretty rich arguments, if you like arguments.

I’m not sure exactly how I’m going to approach the next election where I live, but I will vote. I’m pretty sure I’m always going to vote now, for someone, even if it’s just to enjoy the walk to the polling station. I still believe that in order to be involved in the electoral process in a meaningful, consequential way, a person has to do much more than vote. I can’t vote for our next president tomorrow because I’m Canadian.

There may be other reasons to vote, even if you understand that your chances of influencing the outcome of the presidential election are much smaller than your chances of dying in a car accident on the way to the poll. For some people, voting time serves as a reminder to re-familiarize themselves with the big issues and personalities in the news, by researching platforms and watching debates. It also feels good, it really does. It feels good to talk about. It feels good to find people who think the same way about something as you do. It feels good to see the whole populace (or maybe half) appear care about the same thing. Read More

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

It all pretty the opposite if you're not in the US :) Since 2022 I've changed 3 countries and I'm planning to emigrate to the fourth one. I've had so much novelty and so many things to adapt to. However, time had never run so fast for me as in 2022...