What ADHD is Like (for me)

This is a small collection of some of the ways I believe ADHD has affected my life, mostly adapted from my private journal entries. I posted this page for two reasons:

- To help other people understand what ADHD actually does. ADHD is usually described only in terms of its outward-facing, behavioral repercussions (impulsivity, bad grades, etc). There aren’t many good first-person descriptions of ADHD’s effects out there, and I want to be able to point people to one.

- To help myself understand and manage ADHD’s effects in my life. Writing this out allows me to conceptualize certain challenges in a way I couldn’t in my head. It also helps me articulate its effects more clearly in conversation.

NOTE: This document is currently unedited and intended for browsing rather than reading straight through. It’s pretty rough. Expect typos, weird transitions, non-sequiturs, and redundancies.

General thoughts about ADHD

What does ADHD actually feel like?

A basic summary of the main effects of ADHD as I see it. If you only read one entry on this page, this is probably the most useful one.

One of the reasons I overlooked the possibility of ADHD, despite my many issues, is that I had never heard anyone describe it very well.

It’s usually summarized as a collection of fairly common behaviors, like being hyperactive, being disorganized, doing poorly in school. I had always thought of it as “being really distracted,” which doesn’t capture it at all.

Since I have never not had ADHD, I don’t have direct knowledge of what life would be without it. However, medication has allowed me to experience life with drastically reduced symptoms at times. I’ve also spent my lifetime learning precisely what people without ADHD are expected to do, and medication has made some of those things suddenly possible.

Here’s my interpretation of the main effects ADHD has on the mind.

1. It’s hard to follow most of what you need to listen to, watch, or read.

It’s hard to listen to and comprehend someone’s anecdote, for example. Your attention sort of phases in and out of the story and its meaning many times over the minute or two it takes for the speaker to tell the story. You track the meaning during some moments, and during other moments your attention drifts to other parts or layers of your present moment experience.

This drifting can be very subtle – you may be actively listening and looking at the person, but the attention itself lands somewhere other than the anecdote’s meaning. Over the course of five seconds, you might drift from hearing and understanding the words of the story (“So I went to a movie with Ben…”), to hearing the words but only their sounds, to a tangential concern about part of the story (Hmm I’m surprised Ben would agree to watch a Marvel movie) then back to following the story. These mental diversions can be short, but they’re enough to completely break your understanding of anything that is said, which has immediate and serious implications for learning, socializing, and following instructions of every kind.

The attentional fracturing can compromise any instance of listening, watching, or reading that conveys any sort of narrative or instructions. Books, movies, lectures, anecdotes, your partner’s points during an argument – are all very hard to stay with start to finish. You can imagine how damaging this would be to your efforts to do almost anything.

Especially if you are undiagnosed, it’s not at all obvious that your struggle to meet life’s expectations are an attention problem. Everything just seems really hard.

When I tried medication, it was much clearer what was happening: ADHD makes it so that you can’t seem to listen at the same “speed” as the person is speaking. It’s like you can’t seem to sync up with it, so you’re just white-knuckling the listening process, trying to grasp the vital parts and not look like a jerk. This was especially obvious listening to music after taking the meds – suddenly I could simply hear the music, as it was, without this strange sensation of having to “wrestle” with it in order to listen to it.

The difficulty in staying with something is not necessarily an absence of the desire to listen or comprehend. This point is vital to understanding people with ADHD and treating them fairly.* You can be fully aware of the importance of listening carefully (such as when being given instructions by a police officer, or your new boss during your first day at work) but the attention may still phase in and out, possibly to your anxious thoughts about how badly you need make sure you absorb all of this information.

*Conventional wisdom insists that “paying attention” is a voluntary task anyone can do if they deem it important. If you examine how it works though, attention is clearly more complicated than that. Directing your attention towards something is voluntary, but sustaining the attention there is not –- whether your attention remains where you put it is determined by unconscious processes in the brain. You can test this by trying to pay attention to something boring, like the sensation of breathing. No matter how badly you want to stay with it continuously, the attention moves, on its own, to something else after a few seconds. This drifting is involuntary, and cannot be prevented by forming conscious intentions not to let it happen. You do not get to choose to sustain your attention, only to return it to where it you want it to be. Serious meditation training can strengthen the mind’s involuntary capacity to sustain attention, but even then, this improved concentration is only ever a result of improved conditioning. Sustaining attention may happen more easily and naturally, but it never becomes become voluntary.

2. You can focus really well (or at least normally) on things that are interesting or salient.

While I have trouble following many conversations and instructions, I can become completely absorbed in other tasks and experiences – researching family history, reading a riveting book, watching hockey, or other interesting experiences. This is often called hyperfocus or hyperfixation, and it only seems to happen with activities that are highly stimulating or salient in some way.

This is why ADHDers can concentrate on a video game for nine hours but struggle to complete twenty minutes of math homework. It’s why I would skip classes just to finish a Joy Fielding thriller, but could not bring myself to read the first chapter of Who Has Seen the Wind, or whatever else they assigned in English class.

When an activity is stimulating, it magically allows you to concentrate on it. You feel synched up, compelled, engaged. Attention isn’t perforated like it usually is. Note that “stimulating” doesn’t always mean fun. You might hyperfixate on reliving an argument you had earlier, reading horrible news headlines, or imagining hypothetical scenarios about someone trying to hurt you, or anything else that triggers emotion and immediacy.

I don’t know enough about neurotransmitters to explain hyperfixation on a physiological level. My basic understanding is this: the ADHD brain is deficient in dopamine in certain places, so you gravitate to anything that creates the release of dopamine, which seems to be anything that is stimulating or salient, regardless of its relevance to your well-being or goals.

To manage life, human beings need to be able to focus on what is relevant at a given moment, even when that thing isn’t stimulating or salient. You need to be able to do your taxes on time, even though the novel you’re reading is really getting good. You need to be able to pay attention in a meeting, because what is said is relevant to your job, despite how boring it is.

With ADHD, the ability to do this is drastically compromised. Firstly, you can’t keep your attention on the relevant thing well enough to comprehend the relevant information or do the task. Secondly, you only feel okay when you’re engaged in something stimulating.

The feeling of trying to focus on non-stimulating activities is hard to describe, and it varies by situation. It’s something like trying to do an exam while horns are blaring, reading a book while being driven around in a dune buggy, or plan your next chess move while preventing a cat from hopping up on the couch.

3. Organizing your thoughts and efforts is really hard.

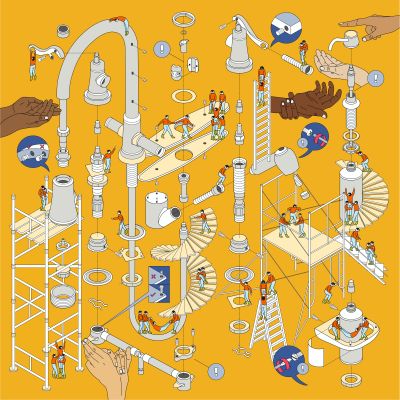

ADHD inhibits something called Executive Function, which is too complex to break down here. Essentially, the executive functions are a set of cognitive processes that help you guide your own behavior toward a goal – knowing what’s relevant to the goal, attending to those relevant things, ignoring what’s irrelevant, maintaining a sense of the overall task and where you are in it, and so on.

Russell Barkley, a prominent ADHD researcher, summarizes the main issue of ADHD as difficulty directing one’s efforts towards a goal. “Goals” in this context include the long-term (become a doctor) and short-term variety (order my Subway sandwich correctly).

A huge factor in managing efforts towards a goal is working memory, which is poor in people with ADHD. You don’t have as big of a cognitive “desktop” to keep several important pieces of information in the mind’s view at once, which is something almost all goals require.

When I’m doing pretty much anything, I find it hard to stay aware of the end result I’m working toward while also attending to the details that will get me there. While I’m engaged with an immediate step (e.g. writing this sentence) I have little sense of what the entire paragraph or article is about, what it might mean to be finished it, and whether the current step is contributing to that.

I can mentally step back and look for evidence of my initial intentions, for example by rereading the first sentence in the paragraph I’m writing. This sometimes works, but doing it for every sentence takes time, interrupts momentum, and often I still cannot regain the sense of quite what I was trying to do. The piece’s general idea might survive the process, but the specific tone and angle that inspired the article often doesn’t. All I can do is plod forward with what I seem to have been doing, and hope I arrive at something useful.

I also lose track of how much time things are taking compared to the scale of the entire task, because I am constantly losing my overall sense of scope and intention.

Here’s an analogy: you’re trying to build a house, but you have to build the entire thing from inside a six-foot tent. You can move the tent freely around the bricks you’re currently laying or the boards you’re hammering, but you can’t see the damn thing all at once and don’t know where you are in it. You just know it’s a house.

With stimulating/compelling tasks (or with medication) this elusive sense of scope and intention emerges. There’s a kind of intuitive “map” of what needs to be done, and a feeling about how each task fits into that overall scheme. Working becomes drastically different. With writing, I usually have to trudge through a weird and confused “in the tent” place for a while, but once I hit on the idea on a compelling way, a clarifying sense of the task emerges. Often I don’t get there at all though.

4. All kinds of secondary and tertiary effects bog down your life.

The attentional and executive function issues inhibit performance at work, in school, in relationships, and every other area of life. That causes a host of second-order problems – social issues, financial issues, costly vices, strained relationships, problems at work, low educational achievement, and so on.

And then those issues cause issues. You have more stress because you can’t get things done and you’re worried about getting fired. You aren’t in the best career for you because you couldn’t finish the schooling. You have low self esteem. You constantly fear bad reactions and disapproval from others. You keep everyone at a distance so they don’t see how dysfunctional you are. You have lower status in society. You’re also in competition your whole life with people who don’t have nearly as many issues.

You tend to organize your life around the things that make you feel okay, leading to overreliance on entertainment, drugs/alcohol, and stimulation-based pursuits that don’t create lasting value. You get in bad relationships. You neglect things with long-term benefits but no short-term rewards, like exercise, saving money, and so on.

The web of problems that can arise from ADHD can be devastating, especially if it’s undiagnosed.

Weird things in my life now explained by ADHD

This is an incomplete list of mysterious issues in my life that my late ADHD diagnosis seems to explain.

Reading books has always been inexplicably difficult.

I love reading. I love the written word as a medium and I believe I have a talent for language and writing. But I’ve never been able to read books the way most people do. I finish maybe ten percent of the books I start, and the ones I finish often take me a month or longer.

The “average reading speed” of 250 words per minute always sounded preposterous to me. That seemed like expert-level reading speed to me, yet I’ve watched many ordinary people knock off novels at a page every minute or two.

As a kid, I preferred nonfiction books with pictures and read mostly the captions and bits of the main text. This was what reading was to me. I was thirteen years old before it dawned on me that people actually read all the words in those thick paperbacks with no pictures. To me that seemed impossible, but apparently they were doing it. It puzzled me that they would want to, because reading never felt that great to me, and they were taking in a massive dose of words. It was like a seeing person eating ten thousand pounds of broccoli. Yet people said it was their favorite thing to do.

I eventually learned that I could read normally if a book happened to grip me in a certain way. One summer my dad gave me Sphere by Michael Crichton, which was the first novel I ever finished. I spent all of August plodding through the first thirty pages, in my usual very-low-comprehension style. (For example, I almost never noticed when characters were introduced, I just noticed when a new name had been appearing in the text more frequently.) At a certain point, something serious happened to the characters (a crew member was killed in a mysterious accident) and I became riveted by a book for the first time. I was suddenly absorbing each sentence, seeing the story unfold like a movie, and I could not stop. I read it all afternoon and all night, and finished it the next day, riddled with goosebumps, while my teacher was taking morning attendance.

That did not happen often. Mostly I stalled in between fifteen and fifty pages in, and never picked it up again.

Like so many unacknowledged-ADHD things, I didn’t realize the problem existed on the attentional level. I knew I was inhibited from reading normally somehow, but didn’t know what to make of it. This is something I’ve always hidden from people, and didn’t even admit to myself.

I knew I wasn’t dumb. I certainly wasn’t illiterate. My trouble didn’t seem like dyslexia, because obviously I can read books properly, somehow, in certain conditions. But I couldn’t create those conditions.

And I did read a lot! I read small things all the time. Articles, blog posts, select bits of books and essays. And I would skim whatever I couldn’t read but wanted to, not quite acknowledging that I wasn’t reading them.

Now that I’m aware of the reason behind my reading difficulty, I can see what is happening when I try to read. Every sentence or two, my attention drifts from the meaning of the words to something else – either their appearance, or something the sentence made me think of, often triggering daydreams or inner monologues that are far more compelling than my uneven, halting experience of reading. I would come back from these diversions eventually, but I now know I don’t necessarily return to the place I’d become distracted, because that wasn’t obvious. I would continue from an arbitrary, easy-to-start-at place on the page in front of me, which would only compound the comprehension issue, making it unlikely I would ever really click with the book.

When reading is so labored, it becomes a lot less attractive. Just imagine if, most of the time you tried to read, somebody whispered some tangential point in your ear every five seconds, or the book would jerk up or down by a centimeter or two every other sentence. It would make reading into an incredibly draining and slow experience, and you would soon stop picking up the book you were reading unless it was amazing. And that’s the experience you have when you know your problem is distraction. Without knowing why reading is so hard, it just feels like a mysterious displeasure comes with the activity of reading itself, regardless of how badly you want to experience the books’ story or learn from its contents.

Serial obsessions

Like many ADHDers I go through short-lived obsessions, then abandon them suddenly. I’ll spend a month or two completely absorbed in some new topic – wine, genealogy, cold war history – to the point of staying up late or skipping class/work to learn more about it. It seems like the most important thing in the world for a while. Then at a certain point the infatuation would just die. Recent obsessions: Napoleonic-era sailing ships, chess, Christian theology. The latest one is jazz drumming.

Social interaction always felt dangerous.

ADHD makes some people talk too much, too loud, too freely. For some of us it manifests the opposite way. I overcompensated for my inclination to say things at inappropriate times by consciously clamping down my own speech, and never saying anything without conscious forethought.

Most of my life, I would try to say nothing around people I didn’t know well, and if I couldn’t, I would mentally review everything before saying it, for possible criticisms or bad reactions. I would flow-chart phone calls before dialing. At all costs, I tried to avoid the nightmare situation, which was having to speak to people I don’t know well without rehearsal or review time. In that case I would white-knuckle my way through the interaction, dying of anxiety the whole time. Unfortunately, most of normal work/school/dating life is this nightmare situation.

I interpreted this terror as “social anxiety,” but honestly I think I’m an extrovert who had to duct-tape himself shut until he developed better strategies. No wonder I took up writing.

Psychologists are increasingly aware that Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is a dumb name and it needs to be changed. Not everyone with ADHD exhibits hyperactivity, and it isn’t a deficit of attention. It has more to do with unusual difficulty in sustaining and organizing intentions, and the many secondary impacts of that difficulty – productivity, socializing, emotional regulation.

Always feeling like people “get” something I don’t

As I went from kid to teenager to adult I felt utterly unprepared for every normal growing-up step: looking for work, becoming comfortable in a job, dating, meeting people, maintaining a household, and fulfilling normal obligations like shopping for Christmas gifts, filing taxes, or returning items to the store. Everybody said, “Well, life isn’t easy!” but I watched as almost everyone else embraced this kind of normal stuff, or at least managed it. To me these tasks felt impossible. I white-knuckled my way through things I couldn’t avoid, and everything else fell through the cracks.

It seemed like other people, regardless of their apparent intelligence or talent, figured out virtually everything more easily. This was confusing because I knew I was smart. I could figure out things I was interested in — sometimes impressing myself and others with how clever I could be — but I just did not have this capacity to figure out necessary-but-uninteresting stuff that almost everyone I knew seemed to have. To use a possibly-relatable metaphor, approaching this stuff felt like reading the Terms and Conditions of the last piece of software you installed, knowing you will be tested on it at some unexpected moment. The dryness is unbearable. You can claw your way through it, but comprehension will be low and results poor.

Difficulty following conversations, excessive self-monitoring, and resulting social anxiety

I want to reiterate that when you don’t know you have ADHD, you don’t necessarily realize you’re having far more trouble doing something than most people are. Whenever I listened to someone share an anecdote or give instructions, I didn’t know it but I was only intermittently following what they were saying. My attention would phase in and out of the content, as I tried to simultaneously earmark the important pieces of information I couldn’t afford to forget. ADHD is characterized by poor working memory, so I couldn’t simply relax and listen, and trust that I would to be able to (a) comprehend fully what was being said, and (b) be ready to respond appropriately when called upon.

This made virtually every social interaction stressful. It’s always a white-knuckled balancing act. I’m trying to listen, while trying to appear like a normal person (posture-wise and demeanor-wise), while drafting a response that will be appropriate should one not occur to me at the exact moment one is expected of me — running three resource-intensive programs at once, all with impaired working memory.

As I moved out of childhood, the self-monitoring became something I was always doing. Believing you generally “don’t get it” has a devastating effect on every aspect of life except spending time alone with your hobbies. Every social activity is difficult when you know you probably don’t get how it works. I always felt like I was always a moment away from revealing my complete inability to be an adult, so I monitored everything I said or did obsessively. I wouldn’t just admit I liked a particular movie, for example, in case I missed the part where everyone decided it was childish or taboo to like that movie. So mostly I said nothing, and when I did say something, I had reviewed it in my mind and determined it would probably go over okay.

The mechanics of my ADHD-related social dysfunction are much more complex than this, but it should give you a hint. Basically, I could not let myself be myself, or I would create a record-scratch moment of some sort. Suffice it to say the anxiety around any unfamiliar interaction (right down to calling a store to ask their hours) was immense.

A specific and intense fear of being put on the spot and asked to explain myself

My poor working memory makes it difficult to explain anything aurally. That’s why I write — because I can’t keep track of complex ideas otherwise. I can’t explain something and simultaneously be aware of which points have been explained and which haven’t, or what level of detail I’m speaking about. If I stop the momentum of talking even for a moment, I will usually forget what I’m trying to say.

Having trouble explaining things aloud causes all kinds of problems, but it’s a particular problem when you have a persistent belief that everything you say risks revealing your general incompetence as an adult. The most intuitive, direct thing to say often felt like the most dangerous thought to venture, because it would undoubtedly reveal how not-normal I am, which would only lead to more interrogation. The scariest moment in the world for me is when somebody asks me to explain myself – why I did or didn’t do something — in front of other people.

It got to the point where I wouldn’t do anything that I didn’t have a canned-and-ready explanation for, because otherwise it’s probably going to be an awkward silence as I scramble for words that make me sound like a competent adult, making me sound guilty and pathetic no matter what I was doing. Often I would repeat this canned explanation over and over mentally as I did the thing, so it would be ready when needed.

This has left me with an intense anxiety around being recorded in any way, because my mink-blanks and non-sequiturs would become permanent evidence that I don’t know how to be a normal person. For this reason I seldom do podcast interviews, and when I do I’m almost in convulsions by the time the interview starts. Usually I cancel pathetically at the last minute and leave the poor podcaster in the lurch. Going on national radio for CBC was terrifying. I basically had an hour-long walking panic attack the whole way there. Once I was in the booth I felt sufficiently trapped that I had to go ahead with it, so I just talked and talked, and I have no idea what I said and I will never listen to it.

Now that I understand the issue (remember I didn’t understand any of this, I just felt the terror) I’m looking forward to challenging this fear, and doing more podcasts and even producing videos. But for now, baby steps.

Almost never achieving long term goals.

I always had a lot of interests, and a pretty clear sense that I am smart and talented and would go places. So I had a lot of goals. Just look at the insanely ambitious bucket list I made at age 29.

As ambitious as I was, and as high as my expectations were (before my midlife crisis began at 38) I almost never achieve goals, except what was already happening as a matter of course.

If it requires a sustained effort and course-correction over time, I will almost definitely not get there.

It’s not because I’m lazy. I put in more effort and pain into not reaching many of goals than would be required to achieve them if I could organize the efforts better. I have struggled with severe procrastination all my life, and I’m just beginning to understand the mechanics of it.

One major effect of ADHD is the poor working memory thing I mentioned. It’s hard to even make a coherent plan for a project, because I can’t see the whole structure at once, on any level. I get lost in details when I’m trying to identify the broad strokes, and I keep get lost in the details concerns about latter steps when I’m trying to sort out the details of step 1. Then there’s the general difficulty of doing anything that I mentioned earlier, which is always operating.

The biggest goal-killer is something even more obscure. I can’t sustain the emotional feel of what it is like to intend to do the project. I can write down all the steps, but I quickly lose the emotional alignment with the project — the feeling of identification with the project as something I will do, which will change my life in some way. Once that happens, I can’t get it back, and it can’t be written down or stored in the plan, because it’s not a thought, it’s a feeling. There’s a kind of a felt motivation needed to sustain action on a project over time. This felt motivation is distinct from the conceptual motivation behind a project (i.e. I should do this because it will have benefits X and Y). I believe this specific emotional deficit has something to do with deficits in the neurotransmitter dopamine. Dr Russell Barkley, a prominent ADHD researcher, summarizes ADHD’s main challenge as “difficulty sustaining an intention over time” and this is my interpretation of the subjective side of that.

Everything I do takes about five times longer than it seems to take others.

There are many factors contributing to this.

Nothing adds more time to a task than procrastination – the period of not doing it before you do it – but let’s leave that out.

It’s hard just to define what the task is. I know I want to clean the living room, but if I just start scrubbing something or picking things up, I can be at it forever and never feel done. The work has to be defined, if not by concept (i.e. a very precise list of tasks) then by some intuitive feeling of what a clean living room is and how to get from here to there. I have those feelings, but I struggle to sustain them.

Then there’s a tendency to slip between level of detail of the task. I can be trying to clean the baseboards, for example, and not be clear on how much effort to apply in removing every spot or smudge before moving on. Executive function is what creates an overall sense of “clean living room” to derive your baseboard-detail-focus level from, so that you end up doing everything to a good-enough level. When I’m doing anything, I have no sense of how large the detail is in the overall context without stopping, standing back and manually calculating all the parts and the time I expect them to take. And that’s just cleaning the damn living room.

There are many more levels to this “takes too long” problem, and in fact I am doing the baseboard over-scrubbing thing in this entry itself. Perhaps that makes the issue as clear as anything I could say.

Like so many issues, simply being aware of this problem enables me to learn to do these things much more efficiently.

I compulsively talk to myself in full monologues or dialogues – out loud when alone, or internally with others.

This is a common ADHD thing. It has two purposes that I can see. It can help clarify my thoughts about something – for example, I often talk out loud when I’m writing, because I can organize an idea more easily than by typing, and it’s too murky if it stays in my head.

The other reason is that monologuing is something I can hyperfocus on. The ADHD brain is always scrounging for an engaging, dopamine-inducing task, and most tasks are not stimulating. However, since I like words and ideas so much, I always have one dopaminergic activity available to me: talking to myself.

This is a good place to point out that a stimulating activity isn’t necessarily pleasant. I easily get drawn into unpleasant political arguments in my head, or imagined scenarios about fighting people or getting attacked by a bear. The brain is looking for something to induce stimulation, and when it finds one it latches on. It has found a lot in my daydreams.

Meditation has been the only thing that has consistently helped me to function, although it is extremely difficult at times.

This topic deserves more time than I have right now. Suffice it to say that meditation helps with self-regulation, concentration, and equanimity, which are especially elusive for ADHDers. Meditation is super helpful for people with ADHD.

Unfortunately, meditation is especially difficult for people with ADHD. In the beginning, it relies on your natural ability to repeatedly bring attention to phenomena that are subtle and often boring. Short term rewards are few and far between. So the learning curve is even steeper for people with ADHD than the general population.

I feel very lucky that my first few experiences hinted at something very significantly helpful, even though I just got a hint of it. Because it did something for me that nothing else did, I never let up at it.

Enjoying certain kinds of entertainment requires a weird kind of effort.

I have always loved music and movies, but it has often felt like it takes a certain kind of persistent effort to enjoy them.

This is most apparent when it’s live – at a concert, or a movie in the theater, I feel like I don’t quite know how to enjoy it, like I don’t know how to settle into the activity of enjoying the show.

For the most part I think it’s an inability to simply stay with the sound of the music or the scenes in the movie. My mind can’t sync up with the speed at which the entertainment is coming into my senses.

(Rare times when I’ve ingested just the right amount of alcohol or cannabis or other substances, I do feel in sync with the experience, and it is truly incredible.)

Another part of this phenomenon is a social spinoff to that – with concerts anyway, I’ve often felt like I need to look like I am effortlessly enjoying the show. I’m very conscious of whether or not I’m bobbing my head to the music, and to what degree, and whether I look like a tool. This feeling of alienation is one example of a greater theme of just not feeling like I belong in the world in the same way others do. If I was a normal person, I would just watch the damn show, but I’m clearly not, so I need to make sure I at least look like one, which is hard to do even while you’re not trying to also do something else, which is effortfully enjoy the concert.

My experiences on medication so far have often produced the amazing feeling of just being able to hear the music in real time (or the conversation, or see the movie). The sense of needing to apply effort is gone. It is so strange, but it feels like it’s how it should be.

I thought I did well in school, but in hindsight I didn’t.

I always thought I was really smart, and got top marks up until about junior high, when I started to get some bad tests and when missed assignments started to have consequences.

The first year of high school, I immediately flunked out of honors math. I had never felt so dumb. In hindsight, one unique aspect of that class is that it was the first time I had no friends in my class – nobody I knew well enough to ask questions of. (I never asked teachers questions.)

When I dropped down to mid-tier math, my class was full of friends again, and I did well.

There’s another factor that helped me do well in school. My dad was a teacher. He was constantly giving me little lessons on math and science, which I thought were neat. They were also very short, and didn’t occur in the deadening, institutional space of a seven-hour schoolday.

Quite often when we learned something in school – particularly math and science – I knew it already. When I didn’t know the material, I could bullshit my way through it, wow the teacher with talent and cleverness, or figure out what answers they wanted on the test based on how it was written. Worst-case scenario, I get a middling mark on the odd thing and my A-pluses average it out to a B+ or A.

If I was struggling with anything beyond that, I had an experienced tutor in the house to help me.

In college, nobody could help me. My marks dropped from A’s on the simple intro stuff in first semester to D’s and F’s in the last.

Weird relationship with food

I always ate portions that were too large, fell too easily for snack foods even when I didn’t like them, ate between means and at times even had a second dinner if I wasn’t too full.

This is a common ADHD thing. Food is a reliable source of stimulation, so you gravitate towards it. Some people find making food (or deciding what to make) so difficult that they forget to eat, or rely on ramen noodles and cereal. Thankfully, I find the process of preparing food rewarding too.

I would often eat until it wasn’t enjoyable anymore, which is much too much. I’ve always marveled at people who would eat a reasonable portion of something and just stop. To me that seemed like deciding not to continue sneezing in the middle of it.

Seeming inability to learn skills beyond beginner/novelty level

I’ve always wanted to play musical instruments and learn languages, and spent not-insignificant amounts of time and effort on them. My guess is that ADHD interacts with long-term-self-directed learning in a number of ways. The reward system that keeps you at a task is inhibited, so there’s a focus issue, especially when it comes to the repetition of running scales or verb conjucations.. It’s also difficult to organize thoughts and efforts around any complex task or goal, and learning an instrument or a language is a massive, amorphous task that requires serious executive function that most neurotypical people never manage. A regular course or teacher would provide structure and organization, but practice needs to be self-directed, and that’s the hard part. In hindsight, it was hopeless to try to learn a language on my own. But I believe I could learn to practice an instrument now that I know what the challenge is.

Extreme rejection sensitivity

This is typical for ADHD, and some people even call it “Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria.” I think that’s a bit too cheeky. Rejection is experienced a lot by people with ADHD, especially if it’s undiagnosed. It’s natural to be unusually sensitive to it if you feel like it’s a major danger for you.

Anger issues

Common as well. I’m not an angry person, but when you’re constantly being expected to do things you absolutely cannot do, anger is an understandable outcome.

There’s another aspect though, and it applies to all strong emotions. When you have ADHD, your brain is hunting for stimulation, and anything salient will do, which includes all strong emotions. I would find myself attracted to reading bad political opinions, and then get angry about them, and rant in my head or out loud about them. I also remember reading sad things or watching sad videos again and again, not because it was pleasant (it’s not) but it was compelling in some way.

“Late bloomer” effect

Also common for ADHD. It is a developmental disorder. It takes longer to figure out ways to do new things and engage with people in new ways, because it’s all on hard mode for you.

A habit of trying to sound smart

I’ve done this this ever since I was a kid. I was always trying to share factoids and other apparent evidence that I am smart or knowledgeable. I still do this and it must come off as really cringey. I think it is mostly an effort to offer evidence that I’m not a bonehead, which is what I often feel like, and another part is the dopamine hit you get when your smarty-pants remark gets some sort of approval.

An account of the moment I was sure I had ADHD, and what led up to it

When I turned 38, I entered a midlife crisis phase characterized by almost-all-the-time anxiety. I could no longer deny that I had a major problem and didn’t know how to proceed. In response, my body decided to crank up the cortisol, and keep it cranked.

It was horrible. I felt like I was going to die soon. I had the distinct feeling that my good luck, which had always seemed undeserved, had simply run out. I could no longer fake it because I wasn’t going to make it.

It became even harder to do anything. Writing especially became difficult, because I’ve always depended on a certain optimism and playfulness, and those were gone. I also felt a new level of impostor syndrome, because it’s hard to advise people on finding well-being when I was the least “well” I’d ever been.

In March 2020, nearly eighteen months later, while everyone else’s anxiety was spiking because of COVID, mine almost disappeared overnight. It felt like a godsend (not Covid, the drop in anxiety) and I looked forward to getting back to an optimistic and hopefully more productive state. I was too grateful for the sudden relief to question why it happened.

I still didn’t have my mojo back though. I was no longer able to set goals, because they weren’t believable anymore. And despite the relief from the crippling anxiety, productivity was worse than ever. The illusion that I was just around the corner from hitting my stride died around my 38th birthday, and apparently I had always depended on that.

Seeing the productivity drop when the anxiety went away was a major clue to eventually discovering the ADHD. I had been blaming my anxiety for my trouble getting things done, not yet realizing how pervasive my lack of productivity had always been. The anxiety was not the cause. It was the other way around — I had never gotten enough done, and there was suddenly no reason to believe I ever would, and that’s why the anxiety exploded.

During the listless months of spring and summer 2020, I spent huge amounts of my time glued to my phone. I was swiping aimlessly, through an increasingly boring sequence of social media apps, up to eight or nine hours a day.

I felt a kind of “mind fog” growing during this period. I couldn’t locate words in my mind as well as usual, further inhibiting both writing and conversing. I felt dull and resigned, and also smaller and more shameful than usual. I still feel this way, and my guess is that it’s a mild depression that began when things started to feel hopeless. The anxiety was much more prominent for that first eighteen months, but eventually my system must have recognized that the incessant fight-or-flight mode was not helping me to fight or flee from the problem. So I slipped from the hyper-arousal of anxiety to the hypo-arousal of depression. Covid lockdowns, and the resulting social isolation and massive screen time no doubt contributed. I’m hoping the coming combination of warm weather, vigorous activity, in-person social contact, and finally getting things done for once will lift me out of it.

Anyway, one day during this listless summer, I decided to google “How do I stop looking at my phone for eight hours a day?” What mostly came up were posts in ADHD forums by people with the same issue. I began browsing these forums, and saw my weird inner life described perfectly. Not just my issue with the phone, or with productivity, but specifically the behaviors I had always engaged in that other people didn’t seem to. (Mostly the behaviors listed above).

ADHD still didn’t feel quite right, because I had taken the self-assessment test before, and I didn’t do many of things they listed as hallmarks: losing things, making careless mistakes, being late all the time, interrupting others, fidgeting, etc. (I now know I don’t do these things because I’ve been madly hypercompensating for them since I was a kid.) But the accounts of inner life –- how it feels to read, how it feels to listen –- were too exact to ignore.

There was a particular moment when it became undeniable. I was a few days into a Zoom-based meditation retreat. It had been a difficult one, because of the mind fog, but I was still more aware and concentrated than I’d been in months. I had something cooking on the stove, which would take about ten minutes. I decided to use that time to read a two-page essay on meditation that was sitting on the table.

I began to read. A few moments later I noticed a steak knife I’d left on the table, haphazardly pointed at my arm.

And I thought, “What if that knife flew from the table and stabbed me in the arm? How damaged would my arm be? Would the blade go right through or is that a Hollywood thing?”

The thoughts intensified. “What if someone was brandishing that knife in my kitchen right now, trying to stab me? What would I do? I’d have to run into the bedroom and lock the door, but it’s one of those flimsy doors you could definitely work through with a steak knife, so it would only slow the murderer by a few minutes. I’d have to jump out the window, no question. It’s too small to step through, so I’d have to kick out the screen and go feet first (headfirst would be a disaster, being on the second floor). Of course, my shoes are way back at the front door, which means I’d land in my socks in the dewey yellow wildflowers (okay, they’re weeds) growing by the side of the house, which would create that instant wet-sock feeling — normally an awful development but considering the circumstances it would be a small matter. I’d have to run down the back lane, in my wet socks, to my nearest friend’s house – or is that a mistake? Perhaps I should run to a farther friend’s house, to have more of a chance of losing the murderer (let’s be fair – he’s only an attempted murderer at this point) before having to stop and frantically rap on said friend’s window. But the close friend’s schedule is more predictable than the far friend’s, and I’d have a better chance catching her at home…”

Then I came back. Oh right! — I was just trying to read this essay on meditation. I’d made it one and a half sentences in, before being captured for forty-five frantic seconds by this hypothetical murderer scenario.

What dawned on me then was not how bizarre this experience was, but how extremely familiar it was. I know that feeling better than my own name. A similar mental digression happens to me – this is an honest guess – about two hundred times a day.

For the first time, it occurred to me that this extremely normal experience is not normal for others. My friends and family probably don’t find themselves constantly gripped by burning yet irrelevant questions — about how to survive imaginary kitchen assailants, or how much turmeric you can eat before you begin to exude its fragrance — while they’re trying to read, watch a movie, or listen to whoever is speaking.

Eureka. I had found it. It. The it behind my lifelong sense that I’m operating under different rules than everyone else. The reason why reading has always been so slow and weird even though I’m perfectly literate, why I am constantly trying to simulate the appearance of having understood what was just said, why everyone I know has a seemingly masterful ability to comprehend movie plots, why I can barely read through the items on my to-do list, let alone do the things on it, why my car’s transmission finally self-destructed, seven years after assuring the Jiffy Lube guy I would change the fluid next time, why I’m still scrolling through Reddit seventy minutes after noticing I have to pee really bad, and why I have never known the feeling of being top of anything, ever.

***

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

Comments on this entry are closed.