I don’t think my father took days off. He must have, but I don’t think I ever witnessed it. I cannot picture him getting up and doing anything besides some kind of work.

When I would drag myself to the couch at 8am on a Saturday to watch cartoons, he was apparently in the middle of his day, already having built or fixed something.

He would permit himself to read books or watch TV later in the day. But I think the idea of taking a proper day off — where he didn’t build, organize, or otherwise try to advance his lot in life at all — was kind of foreign to him.

I don’t have half the work ethic he did, but recently I noticed I do the same thing: I see my weekends, my days “off,” as additional space for getting a bit more done, even if it’s only the kinds of work I enjoy.

A few weeks ago I found myself taking a true Day Off, in which I deliberately spent the day doing things that have absolutely nothing to do with improving, or even maintaining, my position in life. I had decided spontaneously the evening before: no work, no goals, no attempt to gain anything.

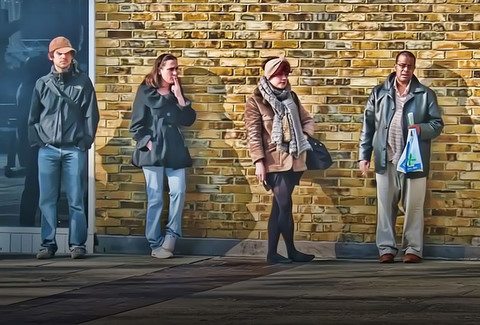

I ended up spending a lot of time outside, and visiting with four separate groups of loved ones, never rushing between them and never thinking much, at any point, about the rest of the day. I spent the morning with my girlfriend, lunch with a friend, the afternoon out walking with my mother, dinner with my sister’s family, and the evening with a book.

I went to bed feeling intensely grateful that my lot in life was such that I could have a day like that, and I slept very well.

If that wasn’t a perfect day then there are none. The biggest difference between that day and a normal weekend day, I realize now, was that I paid little attention to the advance of time. I suspended all aspirations to shaping the future. The only goal was to enjoy the setting and characters of every moment I found myself in, which is refreshingly easy when you’re not trying to get anywhere else.

The next day I went back to work, but I didn’t feel my usual resistance to it, and I got a lot done. The unhurried quality of my Proper Day Off seemed to carry into the following workday. It gave me a distinct feeling of being fine where I was, of not needing to be past what I was currently working on.

The Lost Art of the Day Off

It now seems absurd to let a week go by without a Proper Day Off, and I have quickly become an ambassador for the mostly-lost idea of protecting an entire day from one’s own toil. A lot of us never actually do, whether or not we realize it. We habitually give ourselves jobs on the weekend, and if we accidentally get nothing done, we feel guilty.

Stepping deliberately out of “getting ahead” mode reminds you that you already are “ahead” in all sorts of ways. What’s the point of getting ahead if we never have the experience of being ahead?

Before going on we should clarify what a Proper Day Off actually is. A day off what exactly?

It’s a day off of all the things we do for money, acclaim, position, or out of social obligation; off of treating time like a commodity to be invested or traded for future benefits.

A Proper Day Off isn’t an invitation for laziness, or the shirking of responsibilities. In fact, a Proper Day Off is a day for exploring a certain other class of responsibilities: being a relaxed and present friend, parent, son or daughter, or stranger.

It’s also a time for being a grateful member of civilization. A Proper Day Off is particularly suited to experiencing the highlights of human development: enjoying art, music and public spaces, particularly if we spend the other six days mostly butting heads with the worst parts: inhuman corporations, corrupt governments, vapid celebrity culture, and a news media that delivers only bad news.

6 Principles of a Proper Day Off

A few general rules, to keep your Day Off uncompromised:

1) No work, no “getting ahead”

If getting ahead has any use, it’s so that you can be ahead. A Proper Day Off is reserved for this experience of being ahead — appreciating the fruits of your labor (and that of others) — rather than for laboring even more.

Essentially this means, “Today, do things for now, not for later.” That means no errands, no utilitarian purchases, and definitely no major purchases. In fact, what are you doing in Home Depot at all? Go to the park. And although recreational shopping is a favorite pastime for many people, it is completely inappropriate on a Proper Day Off. Consumer shopping has too many emotional ties to the working world. Refraining from “getting ahead” doesn’t mean a Day Off is best spent getting needlessly behind, by liquidating your hours of labor (and therefore your precious time on this earth) for a low-brow shopper’s high.

Visiting an antique shop, or a farmers market, or a garage sale, is quite suitable for a Day Off — visiting a department store, or (God forbid) a Wal-Mart, is not. Read More

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I'm David, and Raptitude is a blog about getting better at being human -- things we can do to improve our lives today.

I saw someone explain the secret to their success once. It had two steps: 1) Imagine what I'd do if I wasn't lazy. 2) Do that. It sounded absurdly reductive and almost cruel at first, but I've been surprised by how often it actually works. Not all the time, but often enough to...